The Platform

Latest Articles

by Wonderful Adegoke

by Abdul Mussawer Safi

by Mohammad Ibrahim Fheili

by James Carlini

by Mohammad Ibrahim Fheili

by Abidemi Alade

by Sheiknor Qassim

by Theo Casablanca

by Vince Hooper

by Wonderful Adegoke

by Abdul Mussawer Safi

by Mohammad Ibrahim Fheili

by James Carlini

by Mohammad Ibrahim Fheili

by Abidemi Alade

by Sheiknor Qassim

by Theo Casablanca

by Vince Hooper

The ‘G-Word’ and Armenian Genocide Denial in Turkey

Uttering the ‘g-word’ in Turkey is not only taboo but will land you in prison.

In Turkey, speaking the truth about the events of 1915—1923—the forced deportation and massacre of Armenians, Assyrians, Chaldeans, and Pontian Greeks by the crumbling Ottoman Empire—is perilous. Uttering the “g-word” is enough to be branded a traitor, prosecuted, and thrown in prison. Calling for reconciliation with Christian minorities invites the risk of assassination, as seen in the tragic case of Hrant Dink, the Armenian journalist and editor-in-chief of Agos, who was murdered in 2007.

Hrant Dink’s fate epitomizes the dangers of challenging Turkey’s official stance on its history. Prosecuted under Article 301 for “denigrating Turkishness,” Dink’s murder shocked the nation and the world, sparking protests and international condemnation. Yet, his assassin, Ogün Samast, was released on parole for “good behavior” in 2023 after serving just over 16 years. The co-chair of the Human Rights Association, Eren Keskin, commented on X, “Ogün Samast, the murderer of Hrant Dink, was just released. This is such a DYSTOPIC place!! Gültan Kışanak, Selahattin Demirtaş, Osman Kavala, Can Atalay are in prison just because of their thoughts, but the murderer is free!”

Hrant Dink’in katili Ogün Samast biraz önce tahliye edilmiş.Burası böyle DİSTOPİK bir yer!! Gültan Kışanak, Selahattin Demirtaş, Osman Kavala, Can Atalay sadece düşünceleri nedeniyle hapiste ama katil serbest! Ayrımcı İnfaz kanunun sonuçları….

— Eren Keskin (@KeskinEren1) November 15, 2023

Samast’s early release underscores Turkey’s legal system’s entanglement with ultra-nationalist groups. Article 301, enacted in 2005, has become a tool for silencing dissent, especially on the subject of the Armenian genocide. Turkey’s unwillingness to protect Dink, compounded by its failure to prosecute the architects of his murder, reflects a broader pattern: the systematic suppression of truth and the imprisonment of journalists challenging the official narrative.

The Turkish state’s denialism revolves around framing the forced deportation and massacre of over a million Christians during World War I as anything but genocide. Acknowledging this atrocity, scholars like Taner Akçam and Ronald Grigor Suny argue, would upend Turkey’s national mythos. Instead, successive governments have clung to the claim that Armenians were relocated for military reasons, not exterminated. Denialism extends to justifying these actions as a response to an alleged Armenian uprising threatening the Ottoman Empire during wartime, portraying Armenians as traitors rather than victims.

Denial is deeply embedded in Turkey’s foundational history. Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, modern Turkey’s larger-than-life founder, distanced himself from the atrocities but stopped short of demanding justice. In a 1926 interview with Swiss journalist Emile Hilderbrand, Atatürk called the massacres of Christians a “shameful act” and blamed the Committee of Union and Progress (CUP). Yet, despite this admission, the new Turkish Republic neither prosecuted the perpetrators nor pursued reconciliation. Instead, many CUP officials were absorbed into the government, and a general amnesty was declared in 1923.

“These left-overs from the former Young Turks Party, who should have been made to account for the lives of millions of our Christian subjects who were ruthlessly driven en masse from their homes and massacred, have been restive under the Republican Rule,” Atatürk said at the time.

Some scholars, like Masis Kürkçügil, argue that Atatürk’s pragmatism shaped his approach. As a leader navigating the fight for Turkish independence, he could not alienate his allies, many of whom had benefitted from the genocide. The rhetoric of national sovereignty and unity used during the independence movement further entrenched the denialist narrative, portraying Anatolian Turks as victims and Armenians as aggressors. The massacres were reframed as necessary actions to preserve the nation’s integrity.

Turkey’s official historiography, shaped by Nutuk, Atatürk’s seminal 1927 speech at the second congress of the Republican People’s Party, perpetuates this denial. Anatolian Turks are depicted as blameless, while atrocities against Christians are erased. This narrative has been institutionalized in Turkish schools, where textbooks approved by the Ministry of Education present Armenians and other Christians as traitors manipulated by imperialist powers.

Turkish investigative journalist Uzay Bulut perfectly sums up the kind of brainwashing Turkish students go through at schools today. In an article titled “Turkish textbooks: Turning history on its head,” Uzay writes, in part, “Turkey’s Islamist government under President Recep Tayyip Erdogan is preparing to further indoctrinate Turkish school children in propaganda regarding Israel, Greeks, Armenians, Cyprus and other issues of history and geography. New content, named ‘Turkey’s Century Education Model,’ was added to this year’s curriculum and only recently made available for public opinion by the country’s Ministry of National Education. Additions were made in, among other subjects, the ‘History of the Revolution of [the] Turkish Republic and Kemalism’ and geography, specifically relating to Israelis, Greeks, Armenians, Cyprus, and others.”

Turkey’s denialism extends beyond its borders. Since the 1980s, as global recognition of the Armenian genocide grew, Turkey has waged a concerted campaign to counter these efforts. Lobbyists, defense contractors, and NATO membership have been leveraged to stymie genocide resolutions in the U.S. Congress. Even academia has been co-opted; Turkish-funded scholars like Stanford Shaw, Heath W. Lowry, and Justin McCarthy have produced revisionist histories that cast Armenians as rebellious terrorists. High-profile institutions like Princeton University have faced scrutiny for accepting Turkish government funds to support such narratives.

Despite Turkey’s lobbying, the tide of recognition has turned. In 2019, both the U.S. House of Representatives and Senate passed resolutions recognizing the Armenian genocide, and in 2021, President Joe Biden explicitly referred to the massacres as genocide. Yet Turkey’s denial persists, often employing morally dubious tactics. The recent indictment of New York City Mayor Eric Adams for allegedly accepting bribes from Turkish officials to remain silent on the genocide’s anniversary illustrates the lengths to which Turkey will go to suppress acknowledgment.

A path forward requires Turkey to confront its past honestly. As Yetvart Danzikyan, editor-in-chief of Agos, argues, “A healthy society should be able to come to terms with various tragedies, stains, and dark chapters in its history. Turkey, like Germany has done in the past since the Holocaust, would be able to study the past to enlighten its future. Not just Turkey, but each nation such as the UK, the United States, or France should be able to come face to face with the stains in their history for the sake of common good and humanity.”

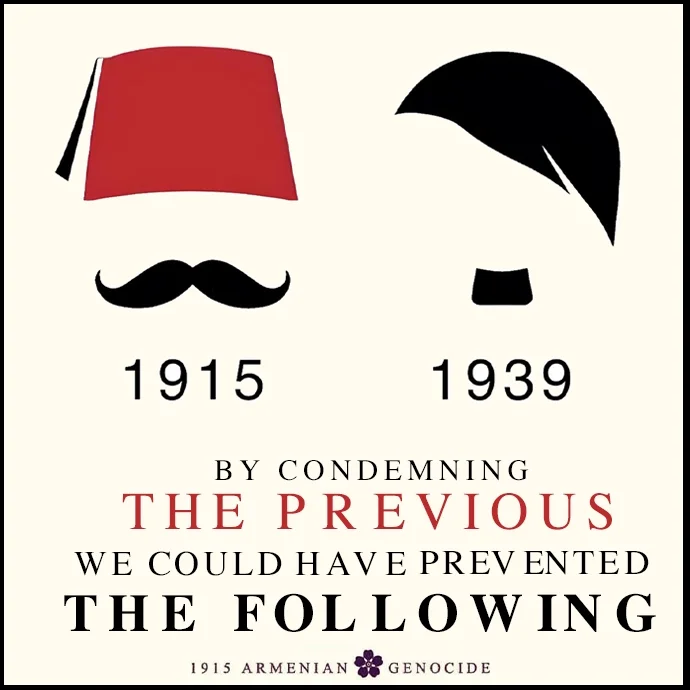

Drawing parallels to Germany’s reckoning with the Holocaust, Danzikyan envisions a future where Turkey engages with its history to build bridges with Christian communities in the diaspora. Meaningful reconciliation—acknowledging the genocide, fostering dialogue, and repairing relations with Armenia, Greece, and others—could transform Turkey’s strained global image.

Instead of investing vast resources into denial, Turkey could focus on initiatives that promote healing and understanding. Acknowledging the genocide would not erase the past, but it could pave the way for a more inclusive and honest national identity. The courage to face history’s darkest chapters is not a weakness but a testament to a nation’s strength and maturity.

To understand the complexities of this issue, it is vital to examine the broader historical and political dynamics that shape denial. Borrowing arguments used by the CUP during World War I, contemporary deniers assert that the deportation of Armenians was a legitimate wartime measure rather than an act of extermination. They claim the death toll is exaggerated, attributing the casualties to disease, famine, and rogue local officials rather than a coordinated campaign. Such narratives shift blame onto the victims themselves, framing Armenians as conspirators aligned with imperial powers.

The legacy of denial was cemented during Turkey’s War of Independence and the early Republican period. Many of the perpetrators of the genocide were absorbed into the fabric of the new state, rewarded with confiscated Armenian properties, and elevated to positions of power. The Turkish national identity, as it emerged, was built on the exclusion and erasure of Christian minorities. This foundational exclusion persists in the rhetoric of contemporary Turkish officials, who invoke the so-called “Sèvres syndrome,” a belief that foreign powers seek to partition Turkey. Acknowledging the genocide is seen not as an act of justice but as a threat to national security.

Education, media, and diplomacy have meticulously cultivated this siege mentality. Turkish history textbooks frame Armenians as traitors who collaborated with foreign powers, presenting their extermination as a necessary defense of the homeland. The government’s narrative is reinforced by its control over academic discourse, with institutions like the Council of Higher Education promoting denialist perspectives. Abroad, Turkey’s lobbying efforts aim to delegitimize Armenian claims, leveraging economic and strategic partnerships to silence critics.

The stakes of denial extend beyond historical memory. For the Armenian diaspora, recognition of the genocide is not merely symbolic but a step toward justice. Reparations, restitution of confiscated properties, and a formal apology are critical components of reconciliation. However, these measures require Turkey to confront its complicity and dismantle the structures that perpetuate denial.

In recent years, there have been glimmers of hope. Grassroots initiatives and independent voices within Turkey have begun challenging the official narrative. Writers, activists, and historians risk prosecution to speak the truth to power, fostering a nascent movement for accountability. Internationally, the recognition of the Armenian genocide by the United States and other nations has provided a moral imperative for Turkey to reckon with its past.

Yet, significant obstacles remain. The entrenched interests that benefit from denial and the government’s authoritarian tendencies stifle progress. The path to reconciliation requires a shift in political will and a transformation of societal attitudes. Education reform, open dialogue, and the inclusion of minority perspectives are essential steps toward a more inclusive understanding of Turkish history.

The cost of denial is measured not only in historical distortion but also in perpetuating injustice. As Yetvart Danzikyan reminds us, the courage to confront the past is a prerequisite for building a more equitable future. Turkey’s refusal to acknowledge the genocide reflects a more profound unwillingness to embrace the diversity that once defined Anatolia. Reclaiming this heritage is not an act of weakness but a testament to resilience and humanity.

For Turkey to move forward, it must abandon the false comfort of denial and embrace the transformative power of truth. The lessons of history demand nothing less.

Ece Çağlar holds a Bachelor’s degree in Politics and Italian from the University of Exeter in the UK. Ece currently runs a textile business in Istanbul, Turkey.