The Shifting Tides of East and West

The narrative of global dominance has long been scripted by the West. Spanning from the classical civilizations of Greece to the geopolitical realities of the 21st century, the term “Western world” has become a cultural, economic, and political touchstone. Yet, this term, predominant since the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, now faces a redefinition. Through the annals of history, Romans, Spaniards, the French, the British, and the Americans have carried their ethos across continents. However, the two-millennium-long Western supremacy is on the brink of transformation.

We now live in a world fragmented into over 200 countries, transitioning from a unipolar system led by American preeminence to a multipolar landscape. This observation, articulated by Zbigniew Brzezinski, underscores the shifting sands of global influence. The once-unquestioned U.S. foreign policy, particularly in the Middle East, no longer holds the sway it once did. Multipolarity is poised to expand as new nations emerge due to factors ranging from rising nationalism in Europe, and historical contexts in sub-Saharan Africa, to geostrategic interests in Asia.

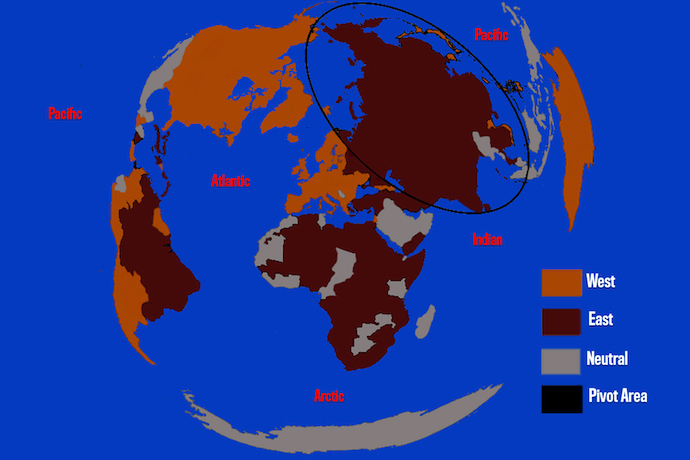

This evolving structure has spawned an uneven globalization. Today, even nations without overt economic or political might can influence the global order. The interconnected vulnerabilities of nations are increasingly palpable because the world no longer orbits around a singular governance model but two: The established West and the emerging East.

While the West represents about 20% of global inhabitants with certain demographic and social metrics, the East sprawls across the majority of the Earth’s landmass. The might of India and China combined accounts for 40% of the global populace, with a staggering 90% of trade navigating their adjacent oceans, the Pacific and the Indian. Africa, where past Western strategies, notably France’s in the Sahel, have faltered, is undergoing rapid industrialization and urbanization. The United Nations projects that Africa’s population will double by 2050, creating a demographic bulwark of youthful individuals.

Today’s global dichotomy, although reminiscent of the Cold War era, is rooted in a different context. This divide is not a result of clashing ideologies but stems from historical colonial legacies and the push for a power shift. A confluence of diverse cultures, ideologies, and governance models seeks to pivot the world’s center of gravity from Europe towards the East. This isn’t merely a binary of NATO juxtaposed against others; it’s a nuanced tapestry of global alliances and interests.

Despite the West’s economic clout, with ten of the top fifteen global economies (U.S., Japan, Germany, UK, France, Italy, Canada, South Korea, Australia, and Spain), the East, represented by China, India, Brazil, and Russia, is gaining ground. Geographic expanses have historically translated to power, and China’s rise is emblematic of this shift.

Africa and the Middle East are emerging as pivotal arenas. Africa remains the only continent devoid of a significant Western foothold. In the Middle East, a nuanced balance of power ensues with Saudi Arabia’s neutral stance and Israel, as the lone Western-aligned nation, navigating a complex web of regional dynamics. Meanwhile, Latin America presents a dichotomy, with Mexico, buoyed by its strategic neutrality, ascending as a significant economic force.

In this fluid landscape, the West should prioritize three regions: Vietnam, the Strait of Malacca, and the Arctic. Cementing ties with Vietnam could be a strategic linchpin for the West in Southeast Asia, particularly in light of the South China Sea disputes. Maintaining the neutrality of critical nations like Malaysia and Indonesia is paramount, given the significance of the Strait of Malacca as a vital trade conduit and a strategic buffer. The Arctic, rich in resources and emerging trade routes, is the next frontier where Russia is keen on asserting its dominance.

The 21st century heralds a new geopolitical epicenter extending from the Arctic to northern Indonesia, delineated by Central Asia and India on one end and the Pacific on the other — an axis that could be termed “Aszuland.” To the south, China’s maritime endeavors aim to reshape trade networks, while to the north, Russia seeks to counterbalance the West in the Arctic race. In this new order, the handful of full-fledged democracies remains rooted in Western soils.