The Truth About the Afghan Economy Under the Taliban

More than two years have elapsed since the Taliban’s return to power in Afghanistan. Since then, the Taliban have been developing a growing narrative suggesting that they are exceeding expectations in managing the economy. This narrative is misleading. The Taliban’s rule paints a picture of a fragile and unsustainable economic situation. Their touted infrastructure achievements are deceptive, and the mining sector continues to face significant challenges.

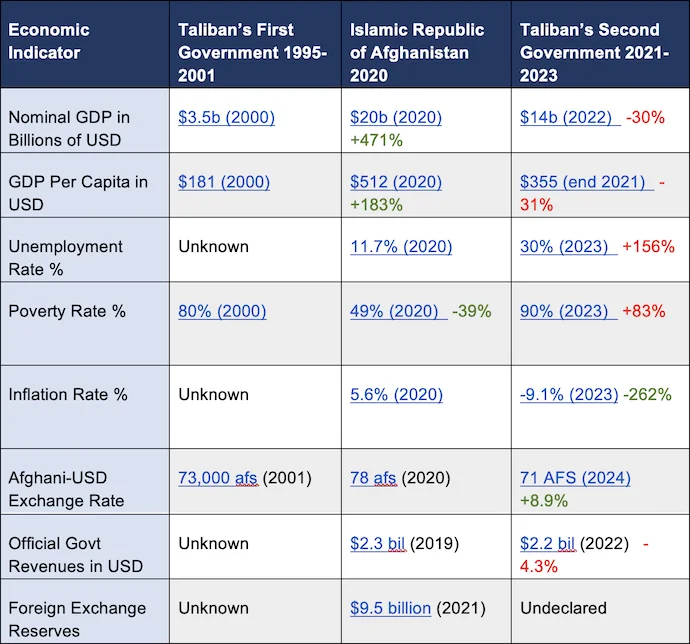

While the Taliban show a stronger currency compared to the previous government, key indicators reverse the picture. Nominal GDP and GDP per capita have plummeted under the Taliban, signifying a decline in average wealth and economic activity. Additionally, unemployment has soared, and poverty rates are rising. Even a seemingly positive sign — a stronger currency — is suspect.

Why the currency’s stability won’t last

A key element of the Taliban’s narrative is the relative strength of the Afghan afghani, the country’s currency, compared to U.S. dollars and other regional currencies. However, this apparent stability isn’t sustainable and doesn’t reflect overall economic health. Once the Taliban prints new currency, it will likely succumb to inflation or hyperinflation.

Some news platforms have even echoed this narrative, characterizing the afghani as the best-performing currency in the world in 2023. However, several factors contribute to this phenomenon.

One factor is the continued inflow of foreign aid, albeit at a reduced level compared to just a few years ago. However, a significant contraction in the Afghan economy has coupled with this. The reduced economic size means a smaller amount of foreign currency can have a proportionally larger impact on the value of the afghani. Essentially, a smaller economy requires less foreign currency to maintain its exchange rate.

The Taliban’s strict controls on foreign currency withdrawals from banks are another factor. These restrictions limit the liquidity of U.S. dollars within Afghanistan, thereby preventing a large-scale sell-off of the afghani and curbing capital flight through U.S. dollar smuggling. However, these controls come at a cost. They impede the free flow of capital and increase transaction costs for trade. This is particularly detrimental to the hawala network, a crucial source of trade finance in Afghanistan due to international sanctions on Afghan banks. Hawala networks rely heavily on cross-border currency transfers.

The Taliban’s implementation of capital controls has mitigated capital flight, albeit to a limited extent. However, the inherent impermanence of such controls creates a conundrum. Easing these restrictions, while necessary to facilitate the smooth flow of trade, will likely trigger a surge in capital flight. The removal of withdrawal limits on bank accounts could similarly lead to a mass exodus of foreign currency and the conversion of savings into foreign assets for transfer abroad, potentially causing a significant devaluation of the afghani.

Wealthy individuals and associates of the Taliban previously partially offset this outflow by shifting their capital from Pakistan into Afghanistan. The Afghan Business Council in Dubai shared with me on multiple occasions that while outflows from Pakistan continue, the class of rent-seeking Afghan businessmen, who flourished during the republic’s war economy, are now aiding Taliban leaders and their associates in finding new havens for their assets, such as Cyprus instead of directing them towards Afghanistan.

The Taliban’s inability to print new banknotes has imposed a form of financial discipline. This printing limitation prevents the Taliban from expanding government expenditures through excessive money creation, a practice that could lead to inflation or even hyperinflation. They rely on heavy taxation of a shrinking private sector, which is a precursor to future revenue generation through seigniorage.

Reliance on seigniorage prioritizes government spending at the expense of currency depreciation and hyperinflation, disproportionately impacting Afghan citizens’ purchasing power. The international community facilitated access to previously printed banknotes; however, this solely replaced damaged or outdated currency, maintaining the overall money supply.

Furthermore, The Taliban’s projected fiscal deficit for 2023 is concerning, with expenditures of $4 billion exceeding projected revenues of $2.9 billion by approximately 40%. Under normal circumstances, governments would address such deficits through borrowing. However, the Taliban’s international isolation precludes external borrowing. The liquidity crisis and lack of surplus capital within Afghanistan’s dysfunctional banking sector also hinder domestic borrowing.

Afghanistan’s widening trade gap also threatens the stability of the afghani.

For a sustainable currency, trade and balance of payments need careful management. While exports rose 18.6% to $2 billion in 2022, according to UNDP, imports skyrocketed 36.7% to $8.2 billion, creating a whopping $6.2 billion trade deficit. External sources such as humanitarian aid, remittances, shady financial inflows, and possibly Taliban asset transfers from Pakistan cover the current gap. But relying heavily on these sources while exports barely grow isn’t sustainable for the Afghan afghani.

The shortfall of the Taliban’s revenue in Afghanistan

In the final years of the Ashraf Ghani government, both the Taliban and the government collected revenues within the country, with the government collecting an annual average of approximately $2.3 billion. After Kabul fell and the government collapsed, the Taliban became Afghanistan’s sole tax authority, creating an expectation of increased domestic revenue.

Despite significantly raising tax rates across various sectors, the Taliban’s domestic revenue collection fell short of the previous government. World Bank data indicates that domestically generated revenues in 2022 amounted to $2.2 billion. The Taliban blame this shortfall on the decline of foreign aid to Afghanistan following their return to power.

However, this explanation overlooks the direct link between reduced aid and the Taliban’s actions. Specifically, their inability to engage meaningfully with non-Taliban Afghans and their failure to secure international diplomatic recognition have hindered their ability to attract continued aid flows.

Due to the transition from insurgency to administration, the Taliban’s local commanders are reluctant to remit all collected revenues to the central authority. Previously, they amassed significant wealth through smuggling and extortion. Now, they receive only modest salaries, leading some to siphon off revenues and others to defect to the Islamic State—Khorasan Province (ISKP) to continue their lucrative smuggling activities.

Taliban rule casts shadow on Afghanistan’s mining potential

The Ghani government made progress in developing the legal and policy framework for the country’s mining sector. However, its efforts to exploit this resource were hampered by the Taliban’s control over vast swathes of rural Afghanistan, where most mines are located. Despite the Taliban possessing firmer control over these areas, this sector faces challenges.

The Taliban prioritizes rapid contract allocation over long-term development. This risks underinvestment and the prevalence of rudimentary, artisanal mining practices. These practices often involve the smuggling of extracted minerals out of Afghanistan, bypassing official channels, and depriving the Taliban of potential tax revenue.

While the Taliban have expedited the awarding of mining contracts in the past two years, primarily to local consortiums with some international participation, these awards have yet to translate into tangible investment. International firms, particularly those from China and Iran who have expressed the strongest interest, remain hesitant due to several factors.

A key concern for these countries is the lack of a clear legal framework. The Taliban’s suspension of the country’s constitution and the absence of a ratified replacement creates uncertainty for investors. Vague references to Sharia law as the legal foundation blur it more. Furthermore, the ongoing sanctions regime against Afghanistan directly impacts the legality of certain mining activities

The continued presence of the Islamic State – Khorasan Province and other Islamist groups within Afghanistan deters international investment as well. Businesses understandably avoid risks tied to potential foreign military intervention by such groups. Notably, the killing of al-Qaeda leader Ayman al-Zawahiri in a U.S. drone strike in Kabul in July 2022 dampened investor interest.

China is frustrated with the Taliban’s tolerance of anti-Chinese Islamist and separatist movements like the Turkistan Islamic Party (TIP) and the East Turkestan Islamic Movement (ETIM). China’s investment pledges are often conditional on the expulsion of these groups, serving as leverage against the Taliban.

Adding to investor uncertainty is the Taliban’s fragile political standing. Their lack of both international diplomatic recognition and internal legitimacy discourages long-term investment. This hesitancy stems from fears of future governments refusing to honor contracts signed under the Taliban. Local Afghan consortiums, viewing the current investment vacuum as an opportunity, are actively seeking mining contracts. However, the limited availability of surplus capital within the economy restricts their ability to capitalize on these opportunities.

The deception behind the Taliban’s infrastructure achievements

The Taliban has actively promoted the construction of the Qosh Tepe Canal and the restoration of the Salang Tunnel as testaments to their infrastructure capabilities. Notwithstanding, the Taliban’s claims of success in infrastructure development are misleading. Their trumpeted infrastructure achievements rely heavily on the groundwork laid by the Ghani government.

The technically demanding aspects of these projects, namely the feasibility studies and design work, were already completed under the previous government. The shortcomings in construction were primarily attributed to the widespread insecurity fueled by the Taliban insurgency, particularly in rural areas where both projects landed. With the Taliban now in power, the security landscape has improved, enabling them to expedite construction at a lower cost. This reduced cost reflects the economic downturn in Afghanistan, with less expensive laborers and machinery compared to several years ago.

Furthermore, the Taliban have touted progress on the TAPI gas pipeline project, claiming efficiency compared to the previous government. The reality, however, is more nuanced. International sanctions directly hinder the construction of the TAPI pipeline. Afghanistan’s underdeveloped legal system throws another wrench in the works, while the ever-present threat of renewed violence continues to impede progress on TAPI.

The Taliban’s commencement of the Qosh Tepe Canal construction has raised concerns in Turkmenistan, particularly regarding environmental consequences and water scarcity. Consequently, the Turkmen government has revived discussions on the TAPI pipeline, seeking non-binding commitments to regain leverage. The renewed focus on TAPI gives the Taliban something to lose if they continue to move on water projects like the Qosh Tepe Canal, disregarding water allocation agreements and canal specifications.

How regional powers are engaging with the Taliban

With the Taliban’s return to power, regional powers have sought to build relationships with them. China’s initial attempt to persuade the Taliban to expel extremist groups has shifted to using conditional economic investment and potential inclusion in a regional project to pressure them on security concerns. However, Russia prioritizes appeasement to minimize extremist spillover, while Iran and Pakistan face challenges due to the Taliban’s harboring of groups they consider threats.

China’s policy towards Afghanistan is driven by a dual concern. Firstly, they fear the destabilizing influence of Islamic extremism on their Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) projects in South and Central Asia. Secondly, they are anxious about the potential spillover of extremism into China’s Xinjiang province. Following the Taliban’s return to power, China initially attempted to engage with the new regime in a persuasive manner. Their objective was to convince the Taliban to expel terrorist groups such as the ETIM and the TIP and to deny safe haven to militants from the Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan (TTP), a group actively disrupting China’s CPEC project in Balochistan, Pakistan.

China has focused on building economic leverage to pressure the Taliban on security concerns. It has conditioned the actual inflow of funds on the Taliban’s cooperation in expelling TTP, ETIM, and TIP from Afghanistan. As a further incentive, China has proposed the inclusion of Taliban-ruled Afghanistan in the CPEC framework, giving the Taliban a stake in the project’s success and a disincentive to support actions that might disrupt it.

Russia and Turkmenistan, acknowledging the security threat posed by a Taliban-ruled Afghanistan, share anxieties about extremism spilling over into their borders. Russia, the primary security provider for Central Asia, fears an increased flow of extremists and ideologies northward. Turkmenistan, concerned about potential refugee resettlement near its border, worries about graduates of Pakistani jihadi madrassas returning to Afghanistan. Turkmenistan sees progress on the TAPI gas pipeline as potential leverage to influence the Taliban’s policies, including deterring them from altering demographics near their borders through refugee resettlement.

To minimize extremist spillover from Afghanistan, Russia prioritizes appeasement of the Taliban, despite long-term security concerns. Stretched thin by the Ukraine war, Russia lacks the muscle to project strength on its southern border, forcing a conciliatory approach towards the Taliban. This appeasement includes facilitating discounted fuel and food exports to help the Taliban government manage inflation.

During their insurgency against the U.S.-backed government, the Taliban courted Pakistan and Iran, aiming to exploit them as safe havens and expecting these ties to translate into dominance after their return to power. Unlike the Ghani government, which clung desperately to the U.S., the Taliban successfully leveraged regional relationships to regain control. Expanded trade routes through Iranian and Pakistani ports were envisioned as the spoils of this strategy.

However, the Taliban’s bungled diplomacy has backfired spectacularly. Their continued harboring of terrorist groups like Jaesh al-Adl, a thorn in Iran’s side, and the TTP for Pakistan have infuriated both nations. This has made it more challenging for the Taliban to secure vital transit routes to the Persian Gulf and Indian Ocean compared to the previous government, contributing to a wider trade deficit.

The fate of Afghanistan’s foreign exchange reserves

The Taliban accumulated negligible foreign exchange reserves by the time their first government collapsed in 2001. In contrast, under the previous government, Afghanistan’s foreign exchange reserves grew significantly, reaching an impressive $9.5 billion, which includes both Afghanistan’s foreign exchange reserves and international investments from private Afghan banks. Following the Taliban’s return to power, the Afghan central bank lost its independence and failed to implement a satisfactory anti-money laundering or combating the financing of terrorism strategy, leading to a freeze on these reserves. Releasing Afghanistan’s frozen reserves might help the Taliban in the short term but could worsen inflation while offering minimal benefits to the Afghan people.

The fate of these frozen funds remains a contentious issue within the international community. Regional powers such as China, Russia, Iran, and Pakistan advocate for their release, arguing that the freeze is a major factor contributing to Afghanistan’s humanitarian and economic crisis. Other countries, such as the United States, believe the Taliban must meet certain conditions before regaining access to the funds. The Taliban themselves have consistently called for the release of the funds, claiming they belong to the Afghan people and they cannot use them as these funds are intended to support the country’s balance of payments and stabilize the Afghan currency.

The Taliban’s desire for the $9.5 billion in frozen foreign exchange reserves raises concerns. Their projected 40% budget deficit in 2023 suggests a troubling lack of fiscal responsibility, prioritizing government spending over economic well-being and Afghan citizens’ needs.

Access to these reserves could be a double-edged sword. The Taliban could auction off U.S. dollars, repurchase banknotes to overprint currency, and inflate government spending. This temporarily mitigates the afghanis depreciation but ultimately leads to increased fiscal spending. Additionally, Taliban-affiliated businesses would likely see a rise in government contracts, further solidifying their grip on power.

However, the Afghan people wouldn’t see significant economic improvement, and their hard-earned foreign exchange reserves could be used to develop Taliban security forces and madrasas. Furthermore, a large portion of the frozen funds belong to private Afghan banks. Releasing them wouldn’t guarantee this money stays in Afghanistan. Given the current instability, capital flight is likely, further diminishing the benefits for ordinary Afghans.

In contrast, while currently inaccessible, these frozen funds are secure, representing deposits made by the Afghan people. Their release should be contingent on the establishment of an internationally recognized government in Afghanistan, be it a reformed Taliban or a new administration entirely. Only then can these funds truly benefit the Afghan people.

The Taliban undermined Afghanistan’s financial system

As the Taliban captured Kabul in August 2021, Afghanistan’s financial sector crumbled. Afghan bank anxieties about looting fueled the decline in activity. Bank leaders worsened the situation by transferring money abroad to falsely blame the Taliban. Thankfully, no looting occurred, but this self-dealing eroded public trust, as bank leaders could not explain the missing funds.

Taliban’s strict Islamic banking rules also hinder the financial sector. Global Islamic banking, despite growth, relies on workarounds within conventional systems. However, the Taliban’s interpretation is more rigorous and leads to dysfunction within the Afghan banking sector. In the absence of a functional stock market, a complete collapse of the banking system triggers a broader financial crisis in Afghanistan, mirroring the situation of the late 1990s.

The Taliban has further exacerbated the situation by suspending insurance companies’ operations and mandating an immediate switch to Takaful (Islamic insurance) or complete cessation of activities. This move threatens to collapse the insurance sector, which would increase business risk and further discourage investment in the country.

Taliban restrictions on bank withdrawals shattered public trust in the banking system. This eroded trust disrupts the flow of money from savers to investors, crippling economic growth. Consequently, the financial sector is likely to shift towards unregulated channels like the hawala system, shrinking the Taliban’s tax base and hindering investment in Afghanistan.

Facing a shrinking financial sector and limited capital, the Taliban are turning to state-owned enterprises (SOEs) to prop up the Afghan economy. In February, they established an independent agency to manage SOEs, suggesting a growing focus on these entities.

While this agency might generate revenue, especially from mining SOEs, these gains are likely exploitative. Local communities and the private sector see minimal benefits, with the latter potentially squeezed out by the dominance of SOEs.

The Taliban are practicing nepotism and misuse of resources

The Taliban’s approach to corruption is a mixed bag. They’ve clamped down on public spending and seem more frugal with national funds. While traditional bribery and kickbacks might be down, new problems have surfaced.

Under the Taliban, nepotism is rampant. Nepotism was blatant corruption under the previous government, but the Taliban saw it differently. Taliban officials’ family members are lining their pockets using their relatives’ power. They push out educated Afghans on purpose. Government jobs go to mullahs and Taliban fighters over qualified professionals. Senior Taliban officials have made public pronouncements that seem to target educated youth. A prime example is the statement by the Taliban’s Acting Minister of Higher Education, prioritizing employment for those who conducted the most bombings in Afghanistan. Every undeserving mullah receiving a salary is a misuse of resources and a form of corruption. It further stifles economic growth and burdens Afghans.

The Taliban’s madrasas construction spree is a misuse of public funds. A World Bank report shows an unprecedented increase in madrasas building across Afghanistan. The Taliban directed tens of millions in 2022 towards new madrasas. While this will spread extremism, the real reason might be financial. Taliban leaders could be diverting state funds through inflated construction costs and by placing family or friends in these institutions, who would then be paid with public money.

The mass exodus of educated Afghans is a major threat. The gradual cultivation of a valuable human capital base stands as the previous government’s primary achievement. This brain drain undermines years of progress in education, both domestic and international. The brain drain in Afghanistan is a two-pronged attack. Inside the country, the Taliban are systematically forcing highly skilled Afghan women out of work and public life. This not only cripples the economy but also risks losing their expertise. Externally, an estimated 2 million individuals have left the country in 2022 alone. The only factor seemingly limiting this exodus is the slow pace of passport issuance by the current government.

Afghanistan’s opium ban fuels a methamphetamine surge

During the Taliban’s 1990s rule, the media often sensationalized their ability to eradicate opium cultivation, though their role as an insurgent group funded by the same trade during the subsequent two decades changed this picture. Following their return to power, the Taliban’s Supreme Leader, Mullah Hibatullah Akhundzada, again banned narcotics cultivation and trade, due to their new control of the state treasury, rendering narcotics revenue less essential. This policy has demonstrably reduced poppy cultivation and marked a verified achievement of the current government.

According to a 2023 report by Alcis, approximately 30,000 hectares of land in Afghanistan remain dedicated to poppy cultivation, with nearly half concentrated in remote areas of northern Badakhshan province. This represents a significant decrease, exceeding an 80% reduction compared to previous years. However, enforcement of this ban relies heavily on Taliban military force.

Failure to address the remaining 20% of cultivation, particularly in remote areas, or to provide alternative livelihoods for affected farmers, could lead to a resurgence. Such a scenario might offer an opportunity for anti-Taliban groups like Islamic State – Khorasan Province and the National Resistance Front of Afghanistan (NRF) to gain local support in rural areas by permitting poppy cultivation within their territories.

Furthermore, neighboring countries like Iran and Tajikistan report a sharp rise in methamphetamines being processed in and exported from Afghanistan. Just like other drug-dealing countries, Afghanistan is shifting towards the more profitable methamphetamine market, explaining their declining focus on heroin.

How aid propels a regime fueling economic uncertainty

The U.S. and NATO withdrawal hasn’t caused a major drop in aid to Afghanistan, but how that aid is delivered has changed. Before, under the previous government, aid went directly into the government budget. Now, under the Taliban, the focus is on humanitarian aid. This means a big funding cut for the security sector, which used to rely heavily on foreign assistance.

The Taliban bolster their regime by using humanitarian aid. A U.S. congressional hearing on Afghanistan showcased it. The Taliban leverage this aid, which covers social services, to free up domestic revenue that they then redirect towards expanding their security forces and jihadi madrassas. Moreover, they generate additional income by forcing NGOs and implementing entities to pay licensing fees. The Taliban further enhanced their financial control through administrative restrictions, such as mandating procurement through Taliban-affiliated suppliers.

Furthermore, the Taliban are pressuring NGOs to include Taliban members or associates in aid projects. This control extends to dictating where aid goes. By controlling the geographical scope of humanitarian interventions, the Taliban can divert aid to areas that benefit their regime.

The influx of humanitarian aid also bolsters the Taliban-led central bank’s foreign exchange reserves. Auctioning U.S. dollars allows them to strengthen the afghani, curbing import inflation. Additionally, a strengthened Afghan currency incentivizes imports, which directly benefit the Taliban through customs duties — Afghanistan’s primary source of government revenue, with approximately 60% derived from customs. Moreover, Afghanistan’s import increase was spurred by currency appreciation in 2023.

Another way the Taliban benefits is through the local procurement of aid goods by NGOs. Since these goods are often imported, the importers pay customs taxes, further enriching the Taliban. Taxes are also levied on profits earned by Afghan banks and money exchanges facilitating these aid-related financial transactions.

While some experts predicted an immediate economic collapse for Afghanistan under the Taliban, the new government has managed a softer-than-expected initial landing. But this fragile stability may not last. Definitions of “collapse” vary, with some arguing it’s already occurred due to widespread poverty and dysfunctional markets. Others warn of hyperinflation if humanitarian aid dries up, while still others see a sliver of hope for a future rebound.