Wes Anderson’s ‘The French Dispatch’ is a Stylish Love Letter to Journalism

Few things in the cinematic world are more instantly recognizable than a Wes Anderson movie. In fact, historically speaking, perhaps only Jacques Tati comes as close to having a signature style easily spotted by viewers. This is Mr. Anderson’s 10th feature film in 25 years, and I now rate 5 of these very highly, though all 10 have a certain appeal. The French Dispatch, co-written by Anderson with frequent collaborators Roman Coppola, Hugo Guinness, and Jason Schwartzman, could be considered his most ambitious to date…and likely the most ‘Wes Anderson’ of all.

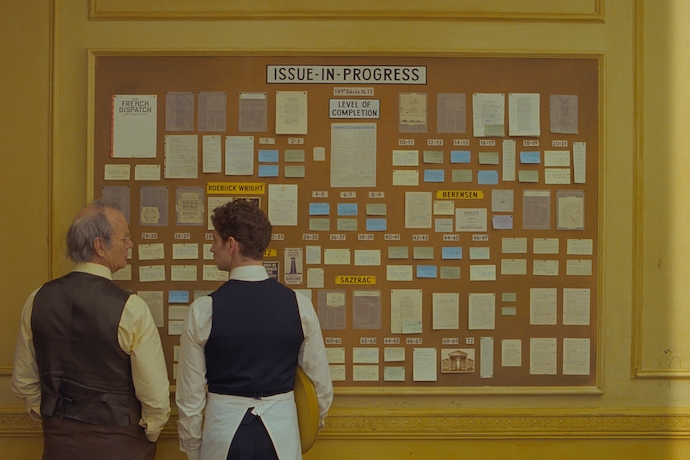

Billed as a love letter to journalists, it becomes crystal clear, that by this, Anderson means the esteemed stable of writers from the early days of The New Yorker. In fact, Anderson structures the film as if it were following the path of a magazine being published. We are informed upfront that this edition features “an obituary, a travel guide, and 3 feature articles.” An episodic format is not unusual for films, yet Anderson never does anything by the book. Each piece takes place in its own time period, and there appears to be little connection or crossover among key characters. Still, somehow he makes this work by ensuring each piece stands on its own and is filled with unusual characters and those patented, fabulous Anderson visuals.

The obituary is that of Arthur Howitzer, Jr. (a deadpan Bill Murray), the founder and publisher of “The French Dispatch” magazine, a spin-off from The Liberty Kansas Evening Sun…a move from a small town in the Midwestern United States to a charming small town in France (hilariously and fittingly) named Ennui-sur-Blasé. Howitzer adores his writers, and the only guidance he offers them is, “Just try to make it sound like you wrote it that way on purpose.” He also has a “No Crying” sign posted in his office, likely as much as a reminder to himself as a rule for the staff.

Our travel guide section is fortunately quite brief since it involves Owen Wilson as a bicycle tour guide showing us around the town – the “Local Color”- of Ennui-sur-Blasé. This takes us to the first feature story, and the best of the lot. Tilda Swinton excels (doesn’t she always?) as a writer and art expert giving a colorful lecture entitled “The Concrete Masterpiece”. She tells the story of Moses Rosenthaler (Benecio del Toro), a genius modern artist serving a life sentence for murder, and as she lectures, we see it play out. While incarcerated, Moses continues to work and his muse is a prison guard named Simone, played exceptionally well by Léa Seydoux. Her nude posing for him leads to his signature modern art piece, which attracts the attention of an ambitious art dealer played by Adrien Brody.

“Revisions to a Manifesto” is the next feature, and it involves a young activist named Zeffirelli (Timothée Chalamet). He’s a chess expert, quite moody, and has a questionable quest. He’s being covered by writer Lucinda Krementz (Frances McDormand), who is unable to maintain objectivity, and inserts herself right into the story, amongst other things. The segment pays tribute to the activism of the 1960s and is filmed mostly in black and white.

The third feature, “The Private Dining Room of the Police Commissioner” involves writer Roebuck Wright (Jeffrey Wright) telling his story while a guest on Liev Schreiber’s talk show in the 1970s. Roebuck is obviously inspired by James Baldwin, and he famously recalls every line he’s ever written. The story he recites involves a legendary chef played by Steve Park.

Actors mentioned so far are just the headliners, and Anderson has packed the film with his usual troupe, as well as dozens of others – some you’ll recognize, and some you won’t. There are at least seven Oscar winners involved: Christoph Waltz, Fisher Stevens, and Angelica Huston (as narrator), in addition to the aforementioned Swinton, McDormand, del Toro, and Brody. Numerous Oscar nominations and awards are included in the group of other familiar faces like Willem Dafoe, Saoirse Ronan, Edward Norton, Lois Smith, Henry Winkler, Bob Balaban, Elisabeth Moss, and Mathieu Amalric.

Other frequent Anderson collaborators who deliver standout work include Production Designer Adam Stockhausen, Cinematographer Robert Yeoman, Editor Andrew Weisblum, and composer Alexandre Desplat. The film looks and sounds remarkable, and somehow it doesn’t feel like it’s moving fast – although we can barely keep pace. The film can be compared to ordering a flight at your local distillery. Each flavor is tasty, but they may not add up to a full drink.

Wes Anderson has delivered another stylish, fun film to watch, and one that is endlessly entertaining. It may not have as many moments of laughter as some of his previous films, yet there are still plenty of sight gags, insider references, and light-heartedness bathed in nostalgia – even if it’s not quite as whimsical. Shot in the French town of Angouleme, the visuals are as impressive as any you’ll find, serving up a collage of time, caricatures, color, and topics.