World Commerce in the Ottoman Empire

Business in the Ottoman Empire was a fluid affair. Early modern trade and mercantilism under the sultanate differed greatly from the highly institutionalized economic practices of the age of globalization. In the absence of institutional frameworks that might otherwise be considered a requisite for international commerce, business was done through a large number of informal cultural institutions centered around the Ottoman household.

Merchants and craftsmen alike operated within larger trade networks, which spanned across cities and into distant realms. These trade routes were effectively social networks, in that they operated by means of interaction between various business-based households, who in communicating and trading with one another created what has been thought of as a “chain of exchange.”

Central to the operation of this chain was the ability of well-to-do merchants to successfully take on limited amounts of risk, in effort to win big at the market. For this they sought investors, often other successful merchants, with whom to share the cost, risk, and profit. These trade agreements frequently sought the greatest plurality of dependable merchants available to efficaciously reduce the risk of losing out on a hefty sum of capital should the trade mission go south. In addition to lowering risks of monetary loss, these agreements helped to establish longstanding friendships, furnishing the mercantile houses with more trusted contacts to conduct their business. The importance of such agreements, in a time when risk-taking in the market could leave one with nothing, cannot be understated. In such a destabilized economic climate, a diversity of friends, as well as products, was essential to financial success.

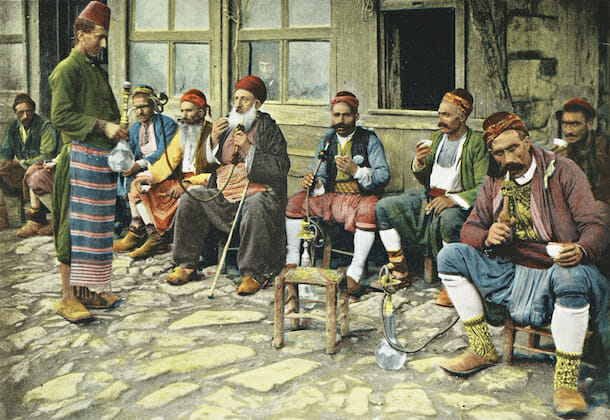

While family firms made up the bulk of businesses across the economic echelons of Ottoman society, travel was necessary for trade. Travel away from well-established bases of operation was full of hazards. For this, the merchants utilized caravanserai, which were small inns which stood on the outskirts of a town, or along the roads of oft-used trade routes, where merchants could congregate relatively safe from the danger of banditry. Because of this, they became renowned outposts of trade in both material goods and valuable information. To this end, we might consider the caravanserai as flickering, but bright, nodes within a vast social network of intersecting lines of exchange, where commodities such as sugar, coffee, pepper, tobacco and silk were moved about the empire.

Despite a working system of exchange based around individual actors and households, businesses operating outside of a governmental framework were not without their difficulties. The lack of standardization in coinage was endemic in the early sultanate, and any successful merchant would have to become accustomed to the variation of weights and measures across a dozen different regions. Additionally, the dangers and statistical problems of traveling over the Ottoman countryside with any large quantity of goods were many.

Eventually, in order to relieve some of the risk in transporting large quantities of money and goods, the widespread usage of IOU’s became a prevalent practice. These were documents that could be drafted by wealthy and respected individuals, stipulating that the holder of it would be paid whatever sum had been agreed upon. Eventually, these documents would be used as a currency in and of themselves in an early model of banking, but there was always a danger that by the time the holder of the document got to the original author, the author might no longer have the funds to pay it.

Guilds filled the vacant role of market controllers. Their existence created an environment that guaranteed quality work from its members for their patrons through standardization of quality, maintained by the setting of prices for products they produced. By setting prices, the guilds prevented the potential for underhanded practices, such as price gouging, by more predatory members of the mercantile elite. These policies largely helped to create market stability for both supply and demand. By controlling the market in such a fashion, the guilds sought to provide some semblance of stability in a less than stable and unpredictable economic environment.

The relationship between the merchant class and the state was generally one of mutual, if hesitant, back scratching. While largely hands-off in allowing the flow of the economy to develop, the state did implement certain policies for the sake of stability, such as focusing on developing wealth within Ottoman borders through merchant houses. The spheres of influence for merchants and state officials most often intersected at trade posts constructed for purposes of protection, taxation, and customs inspections. Customs laws, based largely on Islamic traditions, were enforced, though it was common for such laws to become lax in the presence of a well-placed bribe.

Soldiers also played a role in the world of trade. When working symbiotically with the merchants, they were often hired as bodyguards for long hauls across unpredictable territories. However, this relationship was not always one of benefit to the merchant. It was not unheard of for high-ranking soldiers to flex their military might in an effort to coerce otherwise hesitant merchants into trade agreements.

Overall, the Ottoman economy flourished due to both the sultanate’s direction in promoting Ottoman trade and exports, and due to the merchant houses’ capacity for developing previously unconsidered trade ventures with shared risk. The ability of the Ottomans to adeptly bring imported luxury goods and control their export from then on, allowed the merchants houses vast influence of the international markets and politics of the day.