The Liabilities of History: The Dangers of Pandemic Compensation

Smug assertions of liability in history are often incautious things. They constitute a fruit salad mix: assertions of the wishful thinkers; hopes of the crazed; the quest of genuinely aggrieved generations who feel that wrongs need to be rectified (the Elgin Marbles and transatlantic slavery come to mind). Before you know it, the next historical act will require compensation, the next crime balanced on the ledger of misdeeds. Lawyers will be summoned, writs and briefs drawn up.

The advocates of the China-compensation initiative for COVID-19 are growing in number; most are charmingly untouched by history. Sociologist Massimo Introvigne is one, and with a certain peashooter menace claims that China, especially the Chinese Communist Party “may find itself attacked by an enemy its mighty military power will not be able to stop, aggressive Western lawyers.” Introvigne, while clearly no sharp taloned legal eagle, suggests reference to the International Health Regulations of 2005 which obligates States to conduct surveillance of, and convey accurate and timely information about, diseases through their agencies to the World Health Organization. Tardiness on the issue of reporting outbreaks that can constitute public health emergencies, for Introvigne, might constitute such grave breaches as to violate the Draft Articles on the Responsibility of States for Internationally Wrongful Acts.

These particular articles, drafted by the International Law Commission, are not binding. But the Blame-China lobby has been cunning. James Kraska of the US Naval War College, for instance, thinks that the restatement has been absorbed into the ether of international state practice. Magically, the articles have been constituted as international customary law, which is binding.

A rash of legal suits have appeared across the United States, all sharing one common theme: a guerrilla compensation war via courts against a sovereign state. Members of Congress have been drafting various bills seeking to ease the pathway of private and public suits. Tennessee Senator Marsha Blackburn is one of several, hoping to amend that imposing legal obstacle to suing states known as the Foreign State Immunities Act of 1976 by establishing “an exception to jurisdictional immunity for a foreign state that discharges a biological weapon.” The name of the bill is instructive and leaves little to the imagination, being either the “Stop China-Originated Viral Infectious Diseases Act of 2020” or the “Stop COVID Act of 2020.”

This sort of legal pamphleteering and raging from the stump is interesting but not very instructive. Guilt and agency is already presumed by the advocates: China was not merely negligent in not containing the outbreak of COVID-19, but had actually created the virus with venality. The supreme self-confidence of those in this group leads to problems, the most obvious being the evidence they cite, and much they do not.

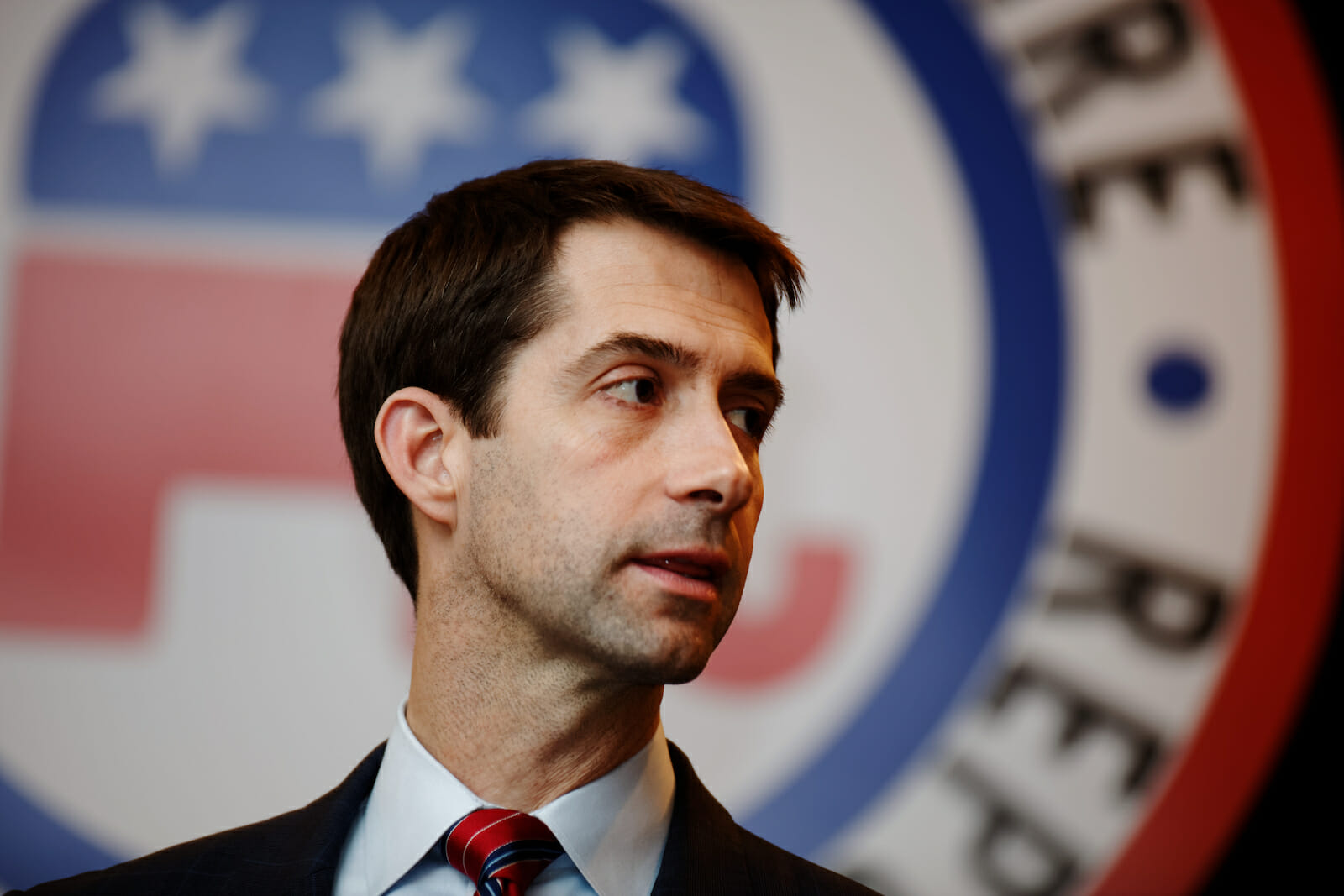

Even if there was something to be made about international pandemic wrongfulness, the United States would surely be one of the first to be cautious in pushing the compensation cart. The measure by Senators Tom Cotton and Josh Hawley, for instance, would grant the US president powers to impose visa and financial sanctions on foreign government officials who “deliberately conceal or distort information” about public health crises. This would also cover associates and those assisting in the endeavour.

But as has been pointed out by more grounded analysts, such measures will simply place US officials in the retaliatory firing line, including those who were rather slipshod with informing the US public about the dangers of the novel coronavirus. Rachel Esplin Odell is convincing in her summation at War on the Rocks: “If applied to Chinese officials, such sanctions would likely invite swift retaliation against US officials who themselves dismissed the threat of COVID-19, shared incorrect medical information about it, or spread false theories about its origins, such as the president, vice president, and many governors and members of Congress – including Cotton himself.”

Odell also warns that using the Draft Articles on State Responsibility in the context of public health is more than mildly treacherous. Disease outbreaks can be unruly things, hard to monitor and track; the customary rule accepting that a state in breach of international law is required “to make full reparation for the injury caused” by that breach has not featured in international health efforts.

David Fidler, a global health specialist, also suggests abundant caution in Just Security for linking state wrongs with infection and disease. What such eager commentators as Kraska avoid is the tendency in state practice to avoid attributing “state responsibility for acts allegedly to be legally wrongful with respect to the transboundary movement of pathogens.” Compensatory mechanisms are absent in any treaty dealing with the spread of infectious disease, and this includes the International Health Regulations (2005).

The pursuit of blame, and efforts to monetise it, also brings to mind the fact that an imperium such as the United States should be reluctant to cast stones in the glasshouse of international politics. That pedestrian dauber yet dangerously inept President George W. Bush might be free to pontificate about COVID-19 and the sweetness of solidarity but remains silent about his misdeeds in ruining Iraq, and, by virtue of that, a good deal of the Middle East. This was an individual who, in March 2003, said that the US would meet the threat of “an outlaw regime that threatens the peace with weapons of mass murder” so as not to do so “later with armies of firefighters and police and doctors on the streets of our cities.” Unlike the case of pathogen transmission, the issue of attribution, in that case, is far from difficult.

While international law furnishes little by way of financial compensation for damage caused by pandemics, it does about the criminal liability of state leaders and military commanders for war crimes and crimes against humanity. It is also worth noting that the foundations for the invasion by the US and its allies was conspiratorial and deceptive, filled with the sorts of fabrications and mendacity that make the bumbling authorities in Wuhan seem childishly modest. In doing so, the crime against peace, sketched by the International Military Tribunal at Nuremberg, was committed. As a Dutch Parliamentary inquiry found in 2010, UN Security Council Resolution 1441, giving Saddam Hussein a final chance to disarm, could not “reasonably be interpreted as authorising individual member states to use military force to compel Iraq to comply with the Security Council’s resolutions.” The warning for US law and policymakers in seeking Chinese scalps should be starkly crystal in clarity.