Culture

Conversation with Photographer Paule Saviano

Portrait photographer Paule Saviano’s work, documenting events and social issues, has been published in magazines around the globe.

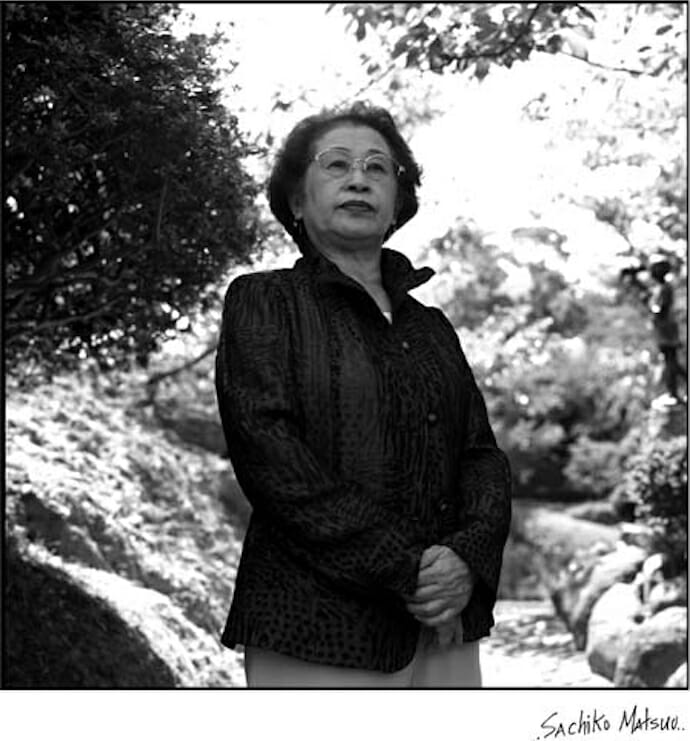

Saviano’s most recent project “From Above” features portraits and testimonies of hibakusha (atomic bomb survivors) from Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and WWII firebombing survivors. The project continues to be expanded to include other cities which experienced the horrors of aerial bombardment during WWII including Dresden, Wielun, Coventry, Rotterdam, and Ústí nad Labem.

“From Above” has been exhibited in museums and galleries in Japan and Germany and, most recently, the United Nations. In August 2011 the project was released as a limited-edition photo book in English, Japanese and German. The book was sold internationally and gathered significant media attention throughout North America, Japan, Europe, and Australia. This award-winning book, through which the project is funded, is available for viewing by going to here.

Saviano’s second book, featuring portraits of people affected by the Berlin Wall and the division of Germany, is scheduled for release in 2018. His next long-term project is to document the lives and transitions of transgender youth and young adults from around the world.

I sat down with Paule Saviano in New York’s East Village. This interview has been edited for length and content. And unless otherwise indicated, quotations come from the interview transcript.

Photographer Paule Saviano wants “From Above,” to educate people on the horrors of war by keeping alive the voices of the hibakusha.

Saviano says: “I really believe that photographs are a universal language…And I want to create for the hibakusha, a permanent visual voice.”

I asked Paule how did he come to document the lives of the hibakusha? “There is a common thread in all my photographs. Whether they are of atomic bomb survivors, hibakusha, or transgender kids. Or the former leader of Communist East Germany. I have tried to photograph people shaped by an event or a time.”

Saviano’s interest in atomic bomb survivors, he says, came from his desire to get an education about the subject- since American history texts don’t often provide information about the survivors. “I began to wonder – weren’t there people there under that mushroom cloud? Did any of them survive? How did they live? What did they think had happened to them?”

In 2007, Saviano began writing to the peace museums in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, with a request – to meet atomic bomb survivors and to hear their stories about the day of the bomb, and then to take their pictures. The people in Nagasaki responded right away.

“We don’t have that kind of thing in American museums. Exhibits tend to be objects under glass cases. With a sign saying: ‘Don’t touch that!’”

“Also, it was an unusual request for the museum. Usually people asked them either to talk to survivors and to hear their stories or to take their pictures, their portraits – not to do both. But they agreed.”

Paule first met with Nagasaki survivors in September 2008, with the assistance of the Peace Museum and the Memorial Hall for atomic bomb survivors. Saviano set up a three day shoot for photographs and interviews. His plan was to take photos and talk with eleven people for two hours each.

Obata was a survivor. But survival is a relative term. It is impossible to talk about the hibakusha without also talking about the pervasive, long-term, deadly sickness caused by exposure to radiation.

During his visit to Nagasaki decades after the 1945 bombing, Saviano learned about the suffering of survivors. Their experience of the shock of the bombings and exposure to radiation never leaves them. And it never leaves their children and grandchildren.

“Radiation sickness has been observed to affect 2nd, 3rd, and 4th generations of hibakusha born to survivors. And the effects of the radiation seem to become worse in later generations. In these 3rd and 4th generation children, cancer rates are much higher than in the general population.”

Survivors of the bomb are marked forever by the experience. “And that mark is never going to go away,” according to Saviano. “And it takes years, for some survivors to process what they’ve been through. Some hibakusha only started speaking out in the early 2000s, 70 years after the bombing.”

Saviano also notes that “hibakusha experience discrimination. Many have a difficult time finding people to marry. Or jobs. Since they have been affected by radiation their insides are different. They experience a greater chance of disease. They continue to be seen as different. It’s kind of a stigma.”

“[Izumi] saw these photos as humanizing the horrors of war. She thought I had taken a warmer approach to the subjects and built trust with them. And Izumi wanted to present the exhibit at her gallery because the gallery [too had been] a survivor of the fire bombings.”

They mounted a full exhibition at Gallery Ef on the 10th of March, 2009, in commemoration of the Tokyo firebombing.

For Saviano, this project is not just a body of work. One might call it a mission. He says that he always tells people in Nagasaki and Hiroshima that they are living in one of the most important places in the world.

“Hiroshima and Nagasaki are the only two places in the world where you can meet people affected by the atomic bombs. Bombs dropped on people- by people. And this is the last generation [of survivors] who can speak directly [about this]. The hibakusha of Hiroshima and Nagasaki are the only people who can tell us that it’s not confetti in those bombs. And when the last hibakusha go silent people are finally going to understand that we don’t have that [witness] anymore.”

Images from the hibakusha project may seem to contradict these points. We see faces, apparently serene. Looking inwards, at peace. They do not display the horrifying scarring we might expect. Yet these faces are also marked by suffering.

Three hibakusha, Sumiteru Taniguchi, Sakue Shimohira, and Senji Yamaguchi, share their testimonies on war, survival, and bearing witness:

“Half a century has passed since peace was restored.

We are in the process of forgetting a painful past.

But I fear oblivion.

I fear forgotten memories are leading to a new affirmation of atomic bombs.”

– Sumiteru Taniguchi“When we walk on the ground,

we should remember that we are walking upon them.

Everyone wanted to survive but many were killed on this spot.”

– Sakue Shimohira“I will continue to fight to the utmost.

No more Nagasaki,

No more War,

No more Hibakusha.”

– Senji Yamaguchi.

I asked Saviano how he had approached survivors of the Tokyo firebombing. The Ef Gallery people and the staff of a small private museum in Tokyo, set up meetings with possible subjects. All told, they found six survivors. And Saviano learned that the story of survivors’ experiences of the Tokyo firebombings was very different from the stories of atomic bomb survivors.

“The experience of the atomic bomb survivors is especially hard for me to imagine. To my understanding…the experience was like, ‘open your eyes, close your eyes, blink, open your eyes again.’ And what you see when you open your eyes again is that everything has been destroyed. In a millisecond. It’s all scorched earth.”

“With firebombs it’s different. Bombs are dropped from the sky. Fire spreads over the course of a night. Fire keeps eating away at everything. You’re being chased by the fire. Crowds of people are being chased by the fire. And this is a terror. To me.”

Saviano said that an argument can be made that most of the Japanese population were affected by firebombs. Tokyo, Kobe, Osaka, the big cities were burned to ash. Women, children, old people- the population died. In fact, more people died in the Tokyo firebombings than from the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombs combined. Yet there is no government compensation, or monument to commemorate victims of the fire bombings – as there is with atomic bomb survivors.

A Tokyo firebombing survivor, Haruyo Nihei, speaking out after sixty years of silence, told him her terrible story. When the bombing started, 8-year-old Nihei ran to escape the flames with her family.

“I survived by the grace of the deceased. People on top of me were all burnt black as a charcoal. They were unidentified till the end and treated as trash. I couldn’t talk about that experience. Even thinking about it was so hard. But to stop the history to repeat, I have to talk. And started talking after almost 60 years,” Nihei recounted.

The project has been expanded to include European firebombing survivors. Saviano has photographed survivors in Coventry and Rotterdam which were firebombed by both the Allies and Germany.

Paule says: “I have made promises to the people in Dresden that I would document the stories of cities firebombed by the Germans…and people victimized by the Germans.”

Remarkably, Saviano was able to photograph two of the handful of Dutch hibakusha who were POWs in Nagasaki. The two were in Nagasaki for a couple of years. Captured in Java, they were brought to Japan, and eventually found their way to Nagasaki. They worked as forced laborers in Mitsubishi factories, and on other projects such as building tunnels, and bomb shelters. Saviano was also struck by their empathy towards the Japanese people.

The story of one Dutch POW named Ron Scholte may illustrate the way one man survived imprisonment and exposure to the bombings, but did not allow his experience to embitter him.

Scholte, born in the Dutch East Indies, joined the Royal Netherlands East Indies Army (KNIL) at the age of seventeen, but the KNIL army surrendered to Japan before his unit was summoned to fight. Scholte was taken prisoner, interned for a year in Singapore, and then sent to Nagasaki to Fukuoka Camp 14, near the Saiwai-machi plant of the Mitsubishi shipyard in Nagasaki. Each POW had a number-his was 254.

Scholte has testified: “I saw a lot of cruelty but after all that I have witnessed, I don’t have any hatred toward the Japanese. I felt that that Japanese were human beings like me. The Japanese were our enemy but my heart was broken when I saw people dying and losing family.”

I asked Saviano how this project has changed him? When did he decide not just to be a student of these events but to become a teacher?

His response: “I don’t consider myself as a teacher. I’m still learning!”

He added: “For me my life has been shaped through the photos I have taken and the people I have met. You can’t have a conversation with me and not mention this subject. It has basically devoured me-who I am!”

Saviano’s next project will be to document the lives of transgender people, with the emphasis on kids. “I really want to spend maybe 20 or 30 years documenting their transition. You can’t do these things if you’re not deeply interested in the subject!”

How did he come to this subject? “The atomic bomb survivors, that subject was presented to me through chance. With transgender people, it was also by chance. I had seen a parade of transgender people demonstrating for their rights and their recognition. If I hadn’t been walking down West 10th St. on a Thursday night, I wouldn’t have seen that parade and probably wouldn’t have become curious…to understand why they wanted recognition.”

Nagasaki, Hiroshima, and Fukushima

It was curator Izumi, says Saviano, who made a sad connection between the hibakusha project and the “accident” in Fukushima-in her own person-through her long exposure to radiation in Fukushima.

Izumi went to Fukushima twice a month, to feed the animals – cats and dogs that had been abandoned, in the evacuation zone. [To my warning that exposure to radiation might be dangerous] she responded: “Listen, you know just how strongly you feel about documenting the lives of hibakusha? I also have this natural urge not to forget the forgotten voices of living creatures.”

Izumi, says Saviano, continued to feed the abandoned animals of Fukushima for a couple of years. “Then two years ago she passed away. She just got sick, and…two months later her doctor told her that she had cancer all over her body. She lasted about a year.”

He commented that just as with survivors of the atomic bombings, radiation poisoning at Fukushima remains a mysterious disease. “We can’t with a 100% certainty say that Izumi’s cancer was from [exposure to radiation] at Fukushima. We’ll never know for certain.”

At the end of our conversation, I asked Saviano if there was a message that he would like to get out to the world through his photographs.

“I want people to understand that the day after a war ends people’s lives don’t go back to where they were before. The effects of that war have an impact on multiple generations. The quick decision ‘Let’s go to war! let’s bomb our enemies!’… it can spiral out of control. Creating a whirlwind of unforeseen circumstances which can’t always be contained.”

“I believe it takes more courage and sacrifice to achieve peace than to fight a war. Peace is imposed without a uniform. It is deemed by the might of compassion- not by the judgment of who is righteous and who is not.”

“There is no victory in war. Only those who have never experienced war view it from the perspective of winning or losing.”