Counting the Cost: Oil Spill Destroys Lives, and Livelihoods in Nigeria’s Delta State

Arinze Chijioke traveled to Opuama, a community in Nigeria’s Delta State, to report on the impact of an oil spill that had devastated many local families.

The time was 10 am in late March. Over 60 women, old and young, gathered outside the house of 90-year-old Julius Loboh, the oldest man in Opuama, a community in the Delta State.

“We are dying. There is no food. Our fish are dead. Our trees are dead. We can’t take it any longer.” The women cried as they got ready to protest the latest oil spill that left one dead and many, especially children, suffering from varying kinds of illnesses.

The men of Opuama had gathered earlier to continue discussions on what to do next after the spill.

Soon, the women got on boats and headed towards the Opuama flow station operated by the Nigerian Petroleum Development Company (NPDC), Elcrest Exploration and Production, and E&P Joint Venture, the companies said to be responsible for the spill.

This is the third time Opuama has experienced an oil spill, with the first happening in 2002 and a second in 2009. But the latest spill has proven to be the most devastating in terms of its spread and impact. In its aftermath, children were stooling and vomiting, suffering severe headaches, stomach pains, and coughs.

Endless spills in the Niger Delta

Nigeria is the largest exporter of oil in Africa and these exports account for a significant portion of the country’s foreign exchange and more than half of government revenue.

This makes it the most exported product in Nigeria with the bulk of the crude oil lying beneath farmlands and rivers in the Niger Delta region.

Sadly, more than six decades of oil spills and gas flaring have transformed the region, which is home to over 6.5 million people whose livelihoods depend on fishing and farming, into one of the most polluted places on earth. These spills have left fishing habitats, swamps, agricultural land, groundwater, waterways, and more in ruins.

Nnimmo Bassy, an environmental rights activist, says the Niger Delta is a place where oil spills occur virtually every day.

After Shell discovered and first pumped oil in Bayelsa in the late 1950s, several international oil companies have exploited Nigeria’s Niger Delta.

While over two million barrels of oil have polluted the region in 2,976 separate oil spills since 1976, about 300 oil spills occur in the region every year. In 2011, a spill at Shell’s Bonga Field released 40,000 barrels. Over 350 farming communities were affected, and 30,000 fishermen were forced to abandon their livelihoods. The people of the Niger Delta have practically watched their futures drain away as a result of oil spills.

An Amnesty International report that exposed evidence of serious negligence in the Niger Delta shows that since 2011, Shell has reported 1,010 spills while Eni, an Italian oil and gas company, has reported 820 spills since 2014.

How it all happened

At 4 am on Sunday, March 14, while families were still asleep, the major oil pipeline from the Opuama flow station ruptured, spilling crude oil. Immediately, news went round that no one should light any cook stoves, or the entire community would go up in flames. The entire Opuama River turned green.

Kintein Chico, a public relations officer for the Opuama Oil and Gas Committee, established to look into cases of oil spills, said the spill was reported and the oil companies immediately shut down operations and gave instruction that nobody should tamper with the spill.

“But a lot of damage had been done by the spill. It covered the whole river so much that you cannot even stand on the river bank. We couldn’t even come out of our houses till the next day,” Chico explained.

The worst hit was the family of Anthony Ebiogbo, a member of the community who died a day after the spill. He had inhaled crude oil fumes. He was said to have complained that he was having a headache and that his eyes were itchy while he was inside his tent.

Community members quickly got medication for him. But he died on Monday and was buried the same day. He had just returned from Lagos where he was selling timber six months ago.

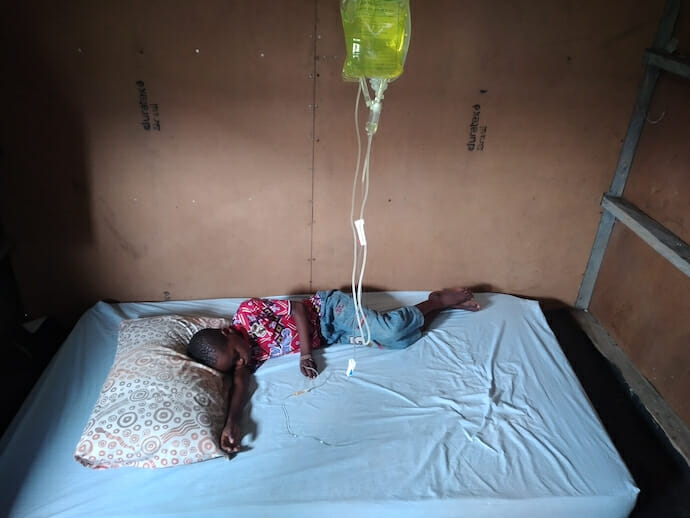

The spill inflicted different kinds of illnesses on children in the community. After inhaling crude oil fumes, they began to suffer from severe headaches, stomach pains, coughs, stooling and vomiting.

They were all taken to a privately owned hospital where they were treated.

It has been endless tears for David Ebiogbo

At the entrance to the tent, just by the side of the door, where Anthony Ebiogbo would normally sit and chat with friends, David Ebiogbo, Anthony’s younger brother, reminisced about the times they shared.

David said his brother would not have died if not for the oil spill that ravaged his community. He said his late brother inhaled the oil fumes after he came out that Sunday morning and couldn’t breathe.

“He held his head and was shouting. We tried to save his life. But he later died,” David said. Since then, David has not stopped grieving. “I never imagined that Anthony would die because of the spill that covered our community,” he said, tears welling up in his tired eyes.

What is also worrying for David is the fact that his elder brother had 13 children with two wives before he died. Although some of them have left home, he said it would not be easy for the family to cope without their father.

“If we knew he would come back and die, we would have asked him to stay in Lagos. But he is gone now,” David said, trying to hold back tears.

The economic impact of the spill

The Opuama oil spill polluted the waterways of the area, killing a lot of fish and damaging the ecosystem. This is highly worrying for members of the community who mostly depend on fishing and timber from their forests for survival.

Before the spill, members of the community only had to walk up to the river, cast their nets, and come back for a full harvest of fish the next day. It was a huge source of income for many families.

But now, there is nothing to harvest. There is nothing to sell. There is nothing to eat. Families who can afford it have to wait for boats from Sapele before they can travel to buy fish.

There is the cost of transportation. There is the risk involved in traveling on the water for hours. There is stress.

Anytime there is no boat, there are no fish.

Oghene Ovo has been married in this community for over 40 years now. But she plans to return to Sapele, where she comes from. She said she can no longer bear the hardship inflicted by the spill anymore.

The day it happened, she was fast asleep and when she perceived the smell of crude oil, she thought it was an electrical fault. After some time, she found it difficult to turn her body and breath. She quickly woke up.

“That was when my neighbor came into my tent to tell me that oil had spilled in the community. I had to go and get drugs,” she explained.

When the day finally broke and Oghene and other members of her community came out of their tents, they could not see water, crude oil had covered everything. “Our fish died. The spill flowed into our creeks and killed a lot of them. Our nets were empty. Now, we are suffering to get fish. We now have to pay N1,500 to get a carton of fish from Sapele. We are hungry. From morning till night, there is nothing to chew,” she lamented.

Hannah didn’t know if her son would survive the spill

When 24-year-old Hannah Uwale perceived the smell of oil fumes at 4 am that Sunday, she quickly got out of her bed. Her 6-month-old son, Ayibasinla, had already started coughing.

Her mother, Tennade Omoko, ignorant of what was going on, had woken up to light a fire to boil water.

When her uncle, Godffrey, heard her trying to light a fire, he quickly called from his room and asked her not to as oil had covered their entire community, she recounted.

At 7 am, her son’s cough had become severe and she quickly ran to a chemist shop to buy him some cough syrup. By Monday, it reduced and Hannah, who teaches at a private school, left her son with her mother. It was her turn to conduct the morning assembly.

But she had only finished saying the morning prayer and was about to take the national anthem when her cousin ran to where she was standing and said her mom was calling her. “I thought she just wanted to see me and asked my cousin to go and that I would join them later,” she said.

Unknown to her, her son had started coughing again. “When we started the matching song, my mom came with my child. He was coughing hard. His eyes were closed and my mom was crying,” she explained.

Immediately, Hannah took her son from her mother and ran to the chemist where he was given several drips before his eyes opened. He only recovered a week later.

Goodluck Ishmael fell at his school’s assembly ground on Monday, a day after the oil spill. 10-year-old Goodluck went to school, like every other child. While he was at the assembly ground and getting ready to go into his classes, Goodluck fell to the ground. He had inhaled oil fumes and had become dizzy, losing control of himself.

Goodluck’s mom, Maria, 35, said her son’s school had to go on break after he fell. She said she and her husband were surprised when they heard that their son had fallen in school because he wasn’t sick before he left home that Monday morning.

“When he fell, his teachers helped him up and one of them quickly called and said my child had fainted. Before I and my husband got to his school, we saw them carrying him and we rushed him to a local clinic,” Maria said.

At the clinic, Goodluck was given some medication and the doctor confirmed that he had inhaled oil fumes. He became well again. But weeks later, while his mother and other women had gone to protest at the flow station, he started throwing up and stooling.

“My husband called to tell me that he had taken my son to the hospital and that I should come back. He was stooling and vomiting. At the clinic, we were told that he still had the fumes in his system,” she explained.

Oil spills and increased newborn mortality

A study by the University of St. Gallen in Switzerland, has found that oil spills that occur within a 10-kilometer radius of human habitation increase the neonatal mortality rate by 38 deaths per 100,000 live births.

Using spatial data and relying on the comparison of siblings conceived before and after a nearby oil spill, the study found that the chemicals can also be dangerous for unborn children in the region if their mothers live too close to an oil spill before the pregnancy begins.

The same study also estimated that in 2012 alone, 16,000 babies died within the first month of life because of oil pollution in the Niger Delta. Generally, children in this region grow up drinking, cooking, and washing with polluted water.

Companies could be held responsible but they don’t seem to care

In 2008, four farmers from the region with backing from Friends of the Earth Netherlands, an environmental group, instituted lawsuits against Shell’s Nigerian subsidiary, Shell Petroleum Development Company of Nigeria (SPDC), in a Dutch court.

This was after leaks from underground oil pipelines cost them their livelihoods by contaminating land and waterways between 2004 and 2007.

On January 29, 2021, the court ordered the SPDC to pay a yet-to-be-established compensation, faulting the company for the environmental destruction caused by pipeline leaks in the affected villages.

While Shell said the leaks were the result of “sabotage” and criminal activities, the court said it could not establish beyond a reasonable doubt that saboteurs were to blame for the leaks that spewed oil over an area roughly the size of 60 football pitches.

The Dutch court did rule that sabotage was to blame for an oil leak in the village of Ikot Ada Udo but insisted that the case over whether Shell was liable would continue.

Although the victory meant that farmers and others who have watched their livelihoods slip away in the Niger Delta can get justice, “getting the companies to behave better is an ongoing battle,” said Nnimmo Bassey, who is the Director of the Health of Mother Earth Foundation (HOMEF).

He said the judgment by the court should be a signal to Nigerian and transnational oil companies to stop their negligence in the Niger Delta.

“It is not like the people of Niger Delta are always looking for cases to take to court to get compensation. They just want a clean environment. With the judgment, it was hoped that companies will behave better. But we are yet to see that happen,” Nnimmo said.

Alagba purged endlessly

Mathew Alagba is the church elder of the Celestial Church of Christ in Opuama. He spoke of how he vomited endlessly after he inhaled oil fumes that Sunday morning.

Mathew said he would have died if he had not been taken to a hospital outside the community to receive medical attention.

“I started purging from 9 pm on Sunday until Monday morning. It was more than nine times. I was cold that Sunday night and that got my wife worried. She had to go and call some elders in the church,” Mathew said.

When the elders got to his house and saw him lying down helplessly, they quickly sent for a doctor who came and ran some tests on him. His blood pressure had gone up as a result.

“[The doctor] started administering treatment on me. He gave me injections and other medications from that Sunday through Wednesday. On Thursday morning, he gave me the last injection and left,” Mathew said.

Five minutes after the doctor left, Mathew began to shiver again. He was all alone this time. His wife had gone out. After boiling and taking warm water, he called one of his church members who ran down immediately.

Other members came too. Mathew asked them to take him to Warri that Thursday. They quickly went and got a speedboat, bought fuel, and rushed him to Warri. When they got to the clinic, they said his temperature was very high.

Mathew was told that oil fumes had occupied his entire system. His legs were shaking. He had to receive further treatment. The doctor said he needed to be admitted for several days.

“They started to flush my system. At one point, my temperature calmed down a little. Every five minutes, I was releasing gas because of the treatment they were giving me. I received an injection through my veins. The stooling reduced and they told me I had malaria and typhoid,” Mathew explained.

Mathew has since recovered.

Accusations and denials

It has been almost one month since the oil spill. But there has been almost no effort by the oil companies involved to clean up the environment. During my visit to the region, oil was still floating on top of the waterways.

But while community members blamed the oil companies for the spill, the companies in turn blamed the spill on saboteurs.

This is not the first time oil companies have been accused of being responsible for contaminating the Niger Delta region through leaks from oil exploration and failing to compensate families.

Persistent spills in the oil-rich region have continued.

On November 10, 1995, Ken Saro-Wiwa and eight other Ogoni leaders were hanged by the military regime of Sani Abacha. Their crime was fighting against oil pollution which had devastated their environment and inflicted poverty and disease on the people.

Five years earlier in 1990, Saro-Wiwa had co-founded the Movement for the Survival of Ogoni People (MOSOP) which launched several campaigns to win compensation for environmental damages as well as demand that the region be given a fair share of oil profits.

25 years later, the killing of Saro-Wiwa and other leaders has watered the seeds of revolution against the Nigerian government and oil companies which has led to the rise of militant groups that attack and burn oil facilities and cause huge revenue losses.

Young men in the Niger Delta are demanding improved regulations and campaigning for their polluted land to be restored.

NPDC refuses to react to the spill

When contacted for comments on the Opuama oil spill, Dahiru Abubakar, the community relations manager for NPDC, refused to speak with me and asked me to direct questions to the external relations department. He could not provide me with any contact information.

I also contacted Tom Abarigho, the community liaison officer for NPDC, through a phone call on April 15. But he said he was not in a position to speak on the matter. He said that the company had previously given its position on the oil spill.

“I am not in the position to answer any question concerning the spill. If you want to ask those questions, you can channel it to the management of the NPDC,” Abarigho said.

Efforts to get through to the management of Elcrest could not yield any result as there was no access to the company’s contact information.

The people of Opuama will not forget the month of March any time soon. It will go down in history as the period when they lost a life to the oil spill.