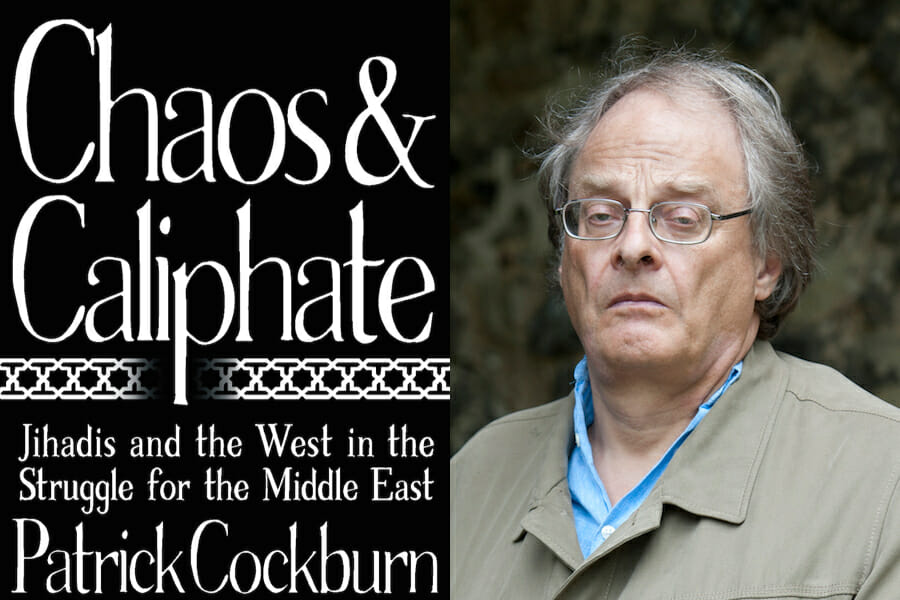

Books

‘From Chaos and Caliphate’

War reporting is easy to do but very difficult to do really well. There is great demand for a reporter’s output during the fighting because it is melodramatic and appeals to readers and viewers. This is what I used to label in my own mind as “twixt shot and shell” reporting and there is nothing wrong with it. The first newspapers were published during the Dutch Wars with Spain, the Thirty Years War and the English Civil War at the beginning of the 17th century. People rightly want to know the latest news about momentous and interesting events such as wars, natural calamities and crime.

But single minded preoccupation with combat may be deceptive, because such exciting events are not necessarily typical; neither do they always tell one who is winning or losing the war. I covered the overthrow of the Taliban in 2001 and the beginning of 2002, which was largely reported as a military victory by the anti- Taliban Northern Alliance supported by US air strikes. Television viewers would have seen impressive pictures of exploding bombs and lines of dejected prisoners. But I followed the Taliban from Kabul to Kandahar and their villages outside the city and saw their forces retreating and breaking up but without really being defeated. There was little serious fighting, but a lot of giving up and going home by Taliban fighters who had been told to do so by their commanders and knew that they were bound to lose the war anyway. At one moment, south of Ghazni, I accidentally drove through the Taliban front line, which had disintegrated. I nervously had to tell my driver to turn the car around and get back as quickly as possible without attracting attention to Northern Alliance positions. I kept thinking that I must have unaccountably missed the real fighting, but finally decided that there had not been much of it. This was important because if the Taliban had not been truly beaten it meant they could make a comeback in the years to come, as indeed they did with spectacular success.

There is a risk here of saying “I told you so” too vociferously, which does no good to the writer or reader. There is also an implied criticism of other reporters as shallow fellows who were caught up in the drama of war and failed to take the longer view. In practical terms, the journalist who spends so much time explaining the whys and wherefores of a conflict and neglects to cover the actual fighting will not hold his or her job for very long.

War reporters are occasionally belittled in two wholly opposite ways as either “hotel journalists,” cowering in their rooms while covering the action second hand, or “war junkies,” tragic figures addicted to the excitement of armed conflict. The first accusation is easily disposed of since those reporters averse to being caught up in a conflict in which they might be killed—not an unreasonable attitude—take the elementary precaution of staying out of dangerous places like Baghdad, Kabul, Beirut, Damascus, Tripoli and the like. As for the allegation that some reporters are “war junkies,” an intense interest in any professional speciality risks giving the impression that one is nursing an unhealthy obsession. But in fact few correspondents are so enamoured with combat that they believe nothing else matters. A surprising aspect of wars since 2001 is that the journalists have often spent a much longer period of time in these countries than Western diplomats or officials. When ISIS captured Mosul in 2014 the political section of the British embassy in Baghdad had just three junior diplomats on short-term deployment.

Of course there may be a certain déformation professionnelle involved in the reporting of wars. When doing so in Afghanistan, Syria, Libya or Iraq, it is difficult not to convince oneself of the significance of whatever skirmish one is describing. This failing is almost impossible to avoid, because everybody is prone to exaggerate the importance of an event in which others are being killed. There is also a natural identification with those soldiers and militiamen, however thuggish and unsavoury, who are being shot at or shelled alongside oneself. Some, but not all, correspondents romanticise rebels who may be heroic defenders of their own communities but are quick to loot and kill when they advance beyond their home ground. All these factors combined in the early days of the uprisings in Libya and Syria to make rebel gunmen sound less sectarian and brutal than they really were. It was only in the first half of 2015 that there was a general admission that, ruthless though the Syrian government might be in barrel-bombing civilian areas, the armed opposition was by then almost entirely dominated by ISIS and Jabhat al-Nusra, the al-Qa’ida affiliate. Sympathetic reporting of rebel-held areas in Iraq, Syria and Libya largely died away because they had become too dangerous for any local or foreign journalist to visit without risking kidnapping or decapitation. As for government-held areas in Iraq and Syria, in the past the Baathist governments in both countries had always made a sort of fetish of their own brutality as a sign of loyalty and determination and regardless of civilian casualties. The Syrian government used the same gangster methods of assassination, bombings and indiscriminate shelling to rule Lebanon during its long occupation as it used against its own civilian population after 2011.

Reporting wars has become much more dangerous now than it was half a century ago. The first armed conflict I wrote about was in Belfast in the early 1970s, when I used to joke that newly formed paramilitary groups appointed a press officer even before they bought a gun. In the first years of the Lebanese Civil War after 1975, the different militias used to hand journalists formal letters telling their checkpoints to allow free passage. There were so many militias that I was afraid of mixing up the letters, which looked rather alike, and used to keep those from left wing groups tucked into my left sock and those from right wing groups into the right one. This relationship broke down from 1984 as Shia fundamentalist groups began to see journalists as targets for abduction for ransom or as political bargaining chips. Iraq at the height of the sectarian warfare of 2006–07 was dangerous, though not as dangerous as it has since become. I used to have a second car tailing mine in Baghdad to see if I was being followed and would make sure the staff in my hotel were well-paid so they could tip me off if anybody was taking too great an interest in my activities. Friends and colleagues who have been killed, such as David Blundy in El Salvador in 1989 and Marie Colvin in Syria in 2012, were very experienced journalists. Once I had imagined that it would be young and over-enthusiastic freelancers trying to make their name who would be killed. In the event, it turns out to have been the veterans who lost their lives more frequently, not because they made any great mistakes, but because they went to the well too often, and got away with it so many times that they took one risk too many.

There is a peculiarity about these present wars that makes them difficult to report because the military activity is not all-out armed conflict. It is a sort of quasi-guerrilla warfare with strong political content, in which the most striking features are the religious fanaticism, cruelty and military expertise of ISIS and other al-Qa’ida type groups that differ little from it in ideology and behaviour, like Jabhat al-Nusra and Ahrar al-Sham. But it is important not to focus only on their attention-grabbing atrocities, but the striking weakness of their enemies, whether they are in Washington or Baghdad. The military prowess of ISIS is less surprising than the speed with which the Iraqi Army disintegrated in 2014 when attacked by far smaller forces. Perhaps this should not have come as the shock that it did: in 2013 I had spent some months in Iraq on the tenth anniversary of the US invasion and decided that the government and army were saturated by corruption and wholly dysfunctional. The following year I had written extensively and begun a book on the growing strength of the extreme Sunni jihadis. Even so, I never conceived that ISIS was going to capture Mosul and most of northern and western Iraq. I had forgotten a golden rule when predicting the future in Iraq, which is to forecast the worst possible outcome, which may take longer to happen than one had expected, but when it does occur will be far worse than one’s direst imaginings. Similarly pessimistic calculations made about Syria, Yemen and Libya in recent years would likewise have accurately forecast their present grim situation.

Excerpted from From Chaos and Caliphate: Jihadis and the West in the Struggle for the Middle East by Patrick Cockburn. Copyright © 2016 by Patrick Cockburn. Excerpted with permission by OR Books.