Inside the Case that Should Have Broken Kenya’s Ivory Cartel — and Didn’t

If an ivory seizure could ever be called “quiet,” this was it.

By global standards, the haul wasn’t especially large. The 216.76 kilograms of elephant ivory recovered in Nairobi in June 2017 fell short of the 500-kilogram threshold typically used to classify a seizure as “major.” But to Kenya’s wildlife crime investigators — and to anyone who follows the illegal ivory trade in East Africa — the case looked explosive. This, they believed, was the rare bust that didn’t just net couriers or drivers, but the financial and logistical core of a transnational trafficking network.

On the night of June 26, 2017, officers from the Directorate of Criminal Investigations’ Special Crime Prevention Unit (SCPU) received a tip: a house in Utawala Estate, near Jomo Kenyatta International Airport (JKIA), was being used to store and prepare ivory for export. The officers kept the address under watch overnight.

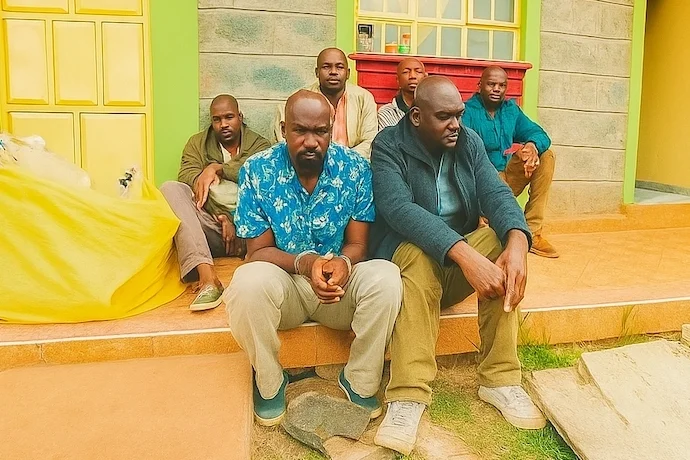

The next morning, at around 10:30 a.m., four SCPU officers moved in. Inside one of the two houses on the compound, they found Julius Abluu Adika, the tenant, alongside Wesley Silvanus Adwenya and Hillary Karani. According to police, the men were in the middle of cutting, grinding, and packaging ivory for air shipment out of Kenya. Two others — Ronson Njue and Rawlings Innocent Ogondi, Adwenya’s brother — were in the vicinity and were also detained. Parked in front of the house was an Isuzu pickup, believed to be the transport vehicle. Njue was thought to be the driver.

What the officers then documented looked like a small factory built for export. In the master bedroom: 64 wrapped pieces of elephant tusk, 25 cylindrical sections of tusk, another 16 hollowed tusk segments, rolls of white and grey tape, and stacks of flattened cartons. In a smaller bedroom: weighing scales, a grinder, and 11 saw blades. In the living room: a strapping machine and a band saw. In the kitchen: a generator. And in the Isuzu: tobacco powder, commonly used by traffickers to mask ivory’s scent from sniffer dogs.

After the search, investigators had Adwenya place a call to the man they believed was the owner of the ivory, Abdinur Ibrahim Ali — also known as Abdinoor Ibrahim Ali. The pretext was an urgent off-site meeting. Ibrahim Ali showed up and was arrested. Kenya Wildlife Service (KWS) officers then arrived to weigh and catalogue the tusks and take custody of the exhibits.

It looked, at first glance, like the classic “smoking gun” case: contraband in plain view, suspects in the act, and a chain to higher-level players. Luck seemed to hold. Three days later, on June 29, officers detained the alleged financier, Ahmed Mahubub Gedi — also known by multiple aliases, including Ahmed Mohamed Salah — at the Namanga border crossing with Tanzania. Gedi was attempting to flee Kenya for Mozambique, where he lived in Nampula. For Kenyan law enforcement, this was the kind of hit they almost never get: a live operation against an organized ivory cartel, with both logistics and money men in hand. It was, arguably, one of the most consequential ivory trafficking arrests in recent Kenyan memory.

Seven men were ultimately charged: Julius Abluu Adika; Abdinur Ibrahim Ali; Wesley Silvanus Adwenya; Hillary Karani; Rawlings Innocent Ogondi; Ronson Njue Mati; and Ahmed Mahubub Gedi. They faced counts of possession and dealing in wildlife trophies, and acting in concert with others under Kenya’s Prevention of Organized Crimes Act. The case entered the record as Republic v. Julius Abluu Adika & Abdinur Ibrahim Ali & 5 others.

International Connections

From the start, investigators and reporters framed the case as a window into a broader cartel. Police statements cast Abdinur Ibrahim Ali as the Kenyan point man for a network that included Guinean nationals in Uganda and Chinese nationals working in Kenya under forged permits. Ibrahim Ali claimed to have ties to a mining concern called Frontier Resources Ltd., based in Bangali, roughly five hours east of Nairobi toward the Somali border.

Gedi, meanwhile, was publicly identified as a Somali national using fake Kenyan documents and acting as the financial broker between Kenyan ivory suppliers and buyers in China and Thailand. The head of the Special Crime Prevention Unit told the press that most of the seized ivory had been sourced from Meru National Park, though another account linked it to the Democratic Republic of the Congo — a reminder that ivory is not only poached locally, but consolidated and laundered regionally through longstanding smuggling routes.

At first, the investigation appeared to be unusually disciplined. Gedi, in a cautioned statement, told police he ran a money transfer service and a travel agency, and that his sole reason for being in Kenya was to act as a financial courier for a West African trafficking cartel. He said he had received $26,000 from a named West African broker based in Bangkok, Thailand, via the Amal Express branch in Eastleigh, Nairobi. He kept $1,000 as his fee and delivered the rest to Ibrahim Ali on June 23.

Adwenya also gave a statement implicating himself at least in logistics. He said Ibrahim Ali had contacted him about sending a consignment to Bangkok. He said he met Ibrahim Ali at Tusky’s Mall in Embakasi, Nairobi, on June 25 (possibly June 23), collected the ivory, and moved it to the Utawala house with Ogondi and Karani.

On July 6, 2017, the SCPU handed the case to investigators at the Kenya Wildlife Service. At roughly the same time, the Ethics and Anti-Corruption Commission (EACC) quietly launched a financial crimes probe, with backing from an international NGO. Their focus: possible laundering of ivory proceeds. At the centre of that strand of inquiry were Ibrahim Ali and Frontier Resources Ltd. What the EACC found suggested that Ibrahim Ali was not just some hired mover. He appeared as a signatory not only on Frontier’s bank accounts, but on the accounts of two other Kenyan firms. Analysis of those accounts pointed to suspicious, high-value transfers — millions of shillings moving out of Kenya in patterns consistent with laundering.

By then, Ibrahim Ali’s links to a well-known West African trafficking cartel were already on record. In February 2017, Ugandan authorities arrested a Liberian national named Moazu Kromah in Kampala. Kromah — along with his brother and nephew — was detained in a fortified compound with 1.3 tonnes of ivory. Documents and emails recovered in that raid connected Kromah, Ibrahim Ali, and Gedi (who Kromah knew as “Ahmedi Fallah”) to earlier ivory smuggling deals.

The EACC also traced money moving through an additional Kenyan figure, then living in Zambia, linked to what was described as a furniture business registered in Hong Kong but physically based in Guangdong, China. Between August 2016 and March 2017, that operation received $1.2 million in transfers from Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda, and Zambia — a regional financial pattern consistent with cartel-level movement of wildlife contraband.

The Nairobi Connection

Beneath the international layer was a more familiar local network. The Utawala house belonged to Julius Adika, who police said ran a vegetable export business. Adika was the uncle of the brothers Wesley Adwenya and Rawlings Ogondi.

Adwenya, in turn, had a direct logistical link to JKIA. He had worked in the flower export trade beginning around 2013, and told investigators he had met Ibrahim Ali a year before the raid and advised him on clearing and forwarding cargo through the airport. Ogondi, his brother, said he was unemployed at the time but had past experience with DHL Global Freight and Swissport Cargo Centre at JKIA. Karani told police he had gone to school with Adwenya and had often seen him at the airport, where Karani was doing casual loading and off-loading work. All four men — Adika, Adwenya, Ogondi, and Karani — were long-time associates from Vihiga County in western Kenya.

Njue, the alleged driver of the Isuzu pickup, lived near Adika and moved goods for the truck’s owner, Raphael Mugenge Kahi, a Ministry of Lands civil servant. Kahi was also from Vihiga County and knew Adika from home. Kahi eventually testified for the prosecution. His written statement cast him as an unwitting participant; his oral testimony, however, hinted at something closer to complicity.

“At the wrong place at the wrong time”

The trial dragged on for eight years. That length, in a case with only 14 prosecution witnesses, was itself a kind of warning light. In Kenya, wildlife trafficking cases often degrade over time — evidence goes missing, witnesses soften, investigators contradict themselves — and prolonged timelines can be a sign that something in the process is being stressed, corrupted, or simply neglected.

On July 23, Chief Magistrate Ann Mwangi acquitted the remaining five defendants. (Adika had reportedly died in April 2022; Gedi had long since vanished.) In her ruling, Mwangi wrote that none of the surviving accused had been found in possession of the ivory recovered from the Utawala house. She said that the records of phone calls between the men did not, on their face, prove ivory trafficking, and suggested that the records might have been “tailored to exclude many other transactions.” She took a similar view of the money transfers between the men through Kenya’s ubiquitous mobile money platform, M-Pesa.

Her decision rested largely on her view of the arresting officers from the SCPU. She wrote that their testimony was not what one would expect from “serious officers who desire to prove” the case and noted that the two officers contradicted each other on basic facts: who was arrested where, who was doing what in the house when police entered, and even who was in the arrest team. On this point, she was right. The prosecution’s own witnesses had shredded their credibility.

In the absence of reliable police evidence, Mwangi chose to believe the accused’s version. This version had benefited from eight years of refinement and had diverged sharply from their initial statements. In that retelling, Adwenya, Karani, and Ogondi had dropped by the Utawala house to check on an ailing relative, Adika. The ivory in the bedrooms, the cutting tools, the band saw, the taped tusks, the generator humming in the kitchen: all of that, they implied, was Adika’s problem, not theirs.

Mwangi embraced that logic. She found that, absent evidence to the contrary, Adika — now deceased — was the guilty party, and that the others had merely been “at the wrong place at the wrong time.” She then did something almost unheard of in a Kenyan ivory case: she declared Adika guilty posthumously of possession and dealing in wildlife trophies. It was an extraordinary move. It also neatly cleared the living defendants.

Hoisted by Their Own Case

In a prosecution already weakened by delay and internal contradiction, the final damage was largely self-inflicted.

Because the EACC’s financial crimes probe was never allowed to mature beyond the investigative stage, prosecutors went to court relying almost entirely on two pillars: the officers who carried out the arrests, and phone data linking the seven accused to one another. That data set included logs of calls among the men, M-Pesa transactions, and rough location information for their phones. But it did not include SMS messages — even though some had been collected — and it did not include deeper analysis of the data beyond call frequency.

The collapse began when the second SCPU officer to testify gave a timeline of arrests that conflicted with the first officer’s account and even with his own contemporaneous written statement from the day of the raid. Suddenly, it was unclear who had been caught doing what inside the house, when Njue and Ogondi had actually been detained, or even how many officers had entered the compound. The only thing the officers agreed on was their claim that they had watched the house all night and seen no movement until shortly before the 10:30 a.m. raid.

But the phone data quietly undermined that story. According to call records, Adwenya, Ogondi, and Karani had not, in fact, spent the night at the Utawala house with Adika, as the police had implied. Instead, they appear to have arrived roughly 45 minutes before the raid — and at least two of them arrived by vehicle. There were also calls between Adika, Adwenya, and Njue in the early morning hours, raising further doubts about the supposed “all-night vigil.”

Most damaging was an SMS from Karani to Adwenya at 9:45 a.m., just 45 minutes before the raid: “Nimefika” — “I have arrived.” That is not the sort of message you send to someone you’ve allegedly been working beside all night in a makeshift ivory workshop. Yet that text never made it into evidence before the court.

In the end, the call data did little more than show that the men all knew each other and spoke frequently. The money transfers between them were, in fact, modest — nothing like the tens of thousands of dollars Gedi said he had moved on behalf of the cartel. Prosecutors referenced a $26,000 transfer to Ibrahim Ali, but because that transfer was mentioned in an SMS sent to someone outside the group of seven, it was never presented in court. The location data was inconsistent and “gappy.” None of it clearly proved possession of ivory, let alone conspiracy to traffic it. The case’s structural supports disappeared in real time.

Where the Evidence Failed

After eight years, almost nothing presented in court definitively linked the central figure, Abdinur Ibrahim Ali, to the ivory found in Utawala. One message that never reached the court record — a 10:15 a.m. text from Ibrahim Ali to Adwenya saying, “Don’t change the booking” — might have offered a starting point for a conspiracy argument. But “might have” never became “did.”

Prosecutors also failed to demonstrate that Adwenya and Ibrahim Ali were in business together for anything other than transport and cargo forwarding. They offered no chain-of-custody evidence tracing where the tusks had originated, who had moved them to Nairobi, how they reached Adika’s house, which airway bill number they were assigned, or which flight or destination was planned from JKIA.

The contradictions in the police testimony effectively erased the presence of Adwenya, Karani, and Ogondi at the Utawala house as incriminating. The Isuzu truck, which could have supported a charge of transporting or attempting to export ivory, was never convincingly linked to a plan to move ivory through JKIA. As a result, Njue, the alleged driver, was no longer able to anchor the contraband. And with Adika dead as of April 2022 — an outcome that mirrors two other major Kenyan ivory cases in which key defendants or witnesses died mid-trial — the living defendants could simply heap responsibility on the deceased.

Incompetence or Interference

Every institution that touched this case — the Directorate of Criminal Investigations, Kenya Wildlife Service, the Office of the Director of Public Prosecutions, and the magistracy — now has questions to answer.

From the moment of arrest, there were signs that someone, somewhere, was working to manage the exposure of one man in particular: Abdinur Ibrahim Ali.

When suspects were first processed, police took a cautioned statement from Adwenya — but not from Ibrahim Ali, who by most accounts was the bigger catch. At the arraignment, Ibrahim Ali’s lawyer asked the court to prevent photography of his client and the others in the dock. That kind of courtesy is not extended to corrupt officials, or even to senior police officers, when they are charged. The prosecution did not object. The court agreed.

In the final two-page police cover report, Ibrahim Ali’s name, the circumstances of his arrest, and his alleged role were all conspicuously absent. Chief Magistrate Mwangi’s acquittal judgment likewise gives him surprisingly little attention. You could call that restraint — after all, very little evidence survived against him. But that absence might itself have warranted comment from the bench.

Then there was the testimony problem. The two SCPU officers could not stick to a coherent account of the arrests. The most plausible explanation is not simple forgetfulness over the course of eight years, but directed perjury.

KWS, which formally took over the investigation on July 6, 2017 — ten days after the Utawala raid — did not, on the evidence presented in court, meaningfully advance it. There is no indication that KWS pursued leads on how long the West African network, via Ibrahim Ali, had been moving ivory through JKIA disguised as “flowers,” or what other consignments might already have moved undetected.

Gedi, the alleged financier and a direct link to Moazu Kromah, was never brought back to court. On July 7, 2017 — just eleven days after the raid — a magistrate released him on $10,000 cash bail, reportedly in an informal, in-chambers session. This is astounding. Here was a foreign national using multiple aliases, arrested while attempting to flee across an international border, carrying a fraudulent Kenyan ID, tied to an alleged transnational organized crime network, and with no fixed address in Kenya. Instead of being remanded, he was allowed to post bond. He disappeared.

His name was later placed on an Interpol Red Notice, but the listing was so thin as to be almost useless. It included none of the basics: no photo, no alias history, no physical description, no charges, not even a mention that he lived in Mozambique. Before the trial ended, his name was quietly taken off the notice.

The conduct of the Office of the Director of Public Prosecutions also raises basic procedural questions. Given how little admissible evidence survived first contact with cross-examination, how did these charges clear internal review in the first place? And once police witnesses openly contradicted their contemporaneous statements, why did prosecutors continue pushing the case instead of acknowledging that it had been fatally compromised?

Even the bench is implicated. In May 2023, Senior Principal Magistrate Samson Temu inherited the file and heard the final three witnesses. He ruled that the state had established a prima facie case — in other words, that there was enough evidence to require the defense to respond. It isn’t easy to square that conclusion with the record, particularly with respect to Ibrahim Ali.

Is it really a coincidence that, across investigators, prosecutors, wildlife authorities, and magistrates, every safeguard collapsed in the same case?

Reprise

Republic v. Julius Abluu Adika & Abdinur Ibrahim Ali & 5 others now join a familiar list of high-profile Kenyan ivory cases that begin in triumph and end in embarrassment. In October 2023, for example, a Mombasa court acquitted nine men — in Republic v. Abdulrahman Mahmoud Sheikh & others — who had been accused of exporting 3,127 kilograms of ivory in 2015. That case, too, involved alleged links to a West African cartel. That case, too, fell apart on contact with the justice system.

Kenya has long positioned itself as an opponent of the international ivory trade. Diplomatically, Nairobi has pushed for strict global controls. Publicly, it has staged high-profile ivory burns and pledged zero tolerance. But inside Kenyan courtrooms, major ivory prosecutions against organized trafficking groups rarely survive. The usual explanation is “lack of evidence.” The persistent suspicion is that evidence is being weakened, withheld, or reshaped.

The Utawala seizure should have been a model. Police found an active cutting and packing operation near the country’s main international airport. They arrested, within days, not just alleged handlers but alleged financiers. They established documented links to an international cartel already known to regional and global law enforcement. The EACC, unusually, got involved alongside KWS, signaling at least some recognition that the case reached into money laundering, not just poaching.

What followed instead was familiar: key suspects insulated, timelines bent, evidence diluted, an eight-year slog, and finally an acquittal that blames everything on a dead man who cannot defend himself.

“At the wrong place at the wrong time,” the magistrate wrote, describing the five living accused. For a case that once looked like a breakthrough against a West African ivory cartel, it is hard to read that line as anything but an indictment of Kenya’s own system.

A special thanks to Judy Muriithi Wangari for her invaluable contribution.