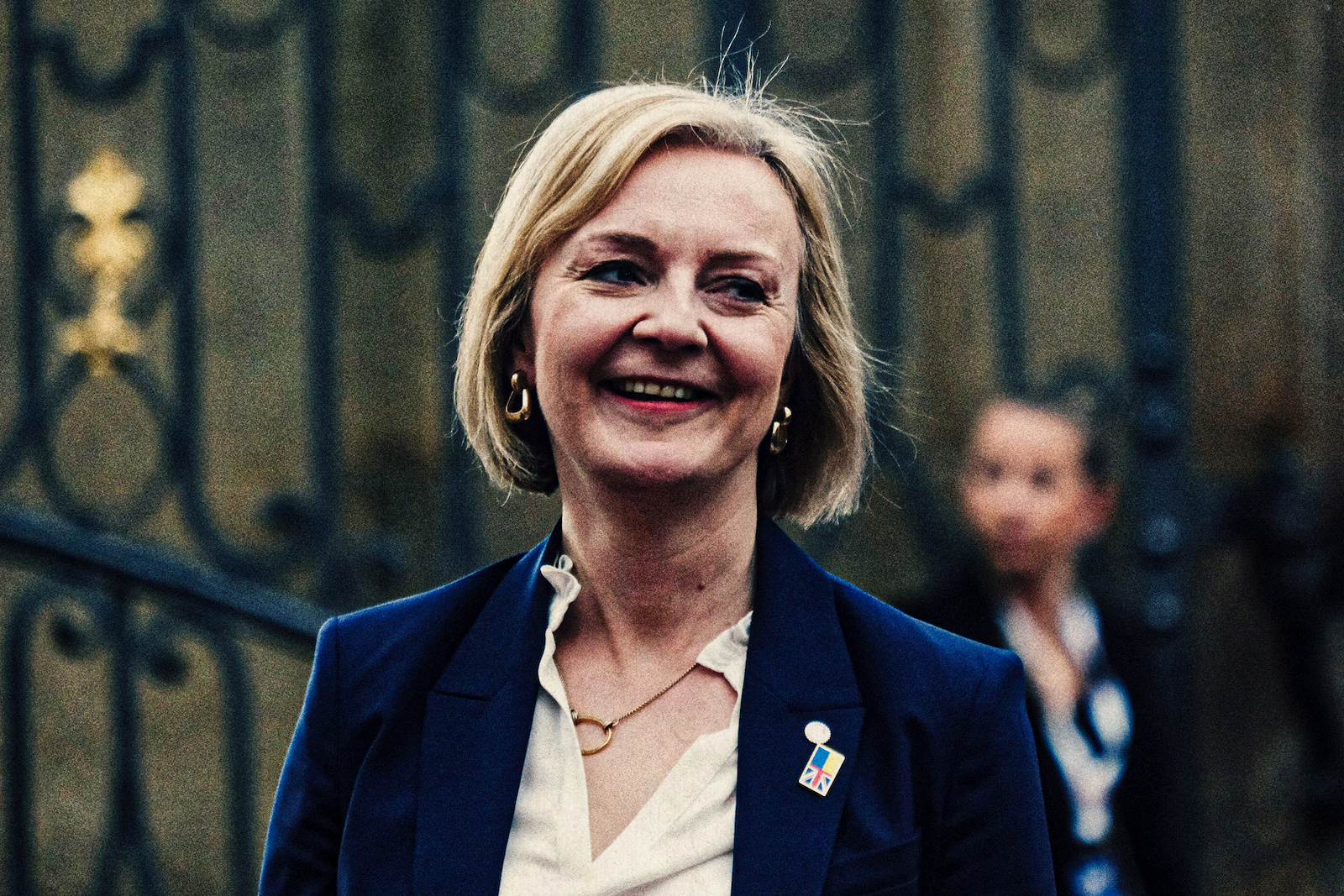

Liz Truss is Now a Case Study in Poor Leadership

Leaders are watched. They are scrutinised. If you don’t like the idea of being held accountable and having to answer for your actions then a leadership role is probably not for you.

I don’t know if such thoughts have ever occurred to Liz Truss, who is still, at the time of writing, Britain’s prime minister. But perhaps the truth is beginning to dawn on her. She has picked the wrong time and place to discover that leadership may not be quite her thing.

As you rise up an organisation there will be greater rewards to accompany greater responsibility. The so-called “tournament theory” of organisational life explains this process quite well.

But with those rewards and responsibilities comes greater exposure to criticism and scepticism. As the crude saying has it: “The higher a monkey climbs, the more you can see its arse.” The sort of mistakes Truss was able to get away with or laugh off as a more junior figure cannot be so easily dismissed now that she is, for the time being, prime minister.

Truss has rapidly become a case study in leadership failure. What have been her most glaring mistakes?

She has been over-confident in her ability, presuming rather glibly that soundbites and repeated statements are an adequate way of delivering leadership. She has placed too much weight on the simplistic free-market ideology which inspires her but does not convince others. Excited thinktank theory has crashed into complicated and less predictable reality.

She has fallen for the mythology surrounding Margaret Thatcher’s time in office, believing in the surface story of her resolute approach and failing to recognise the more subtle truth about how adaptable and flexible she could be.

Above all, Truss has failed to “confront the brutal facts” of her situation – a task considered crucial for good leadership.

She and her (former) chancellor were warned that unfunded tax cuts on such a large scale would cause profound nervousness in the financial markets. She rejected advice, dismissing the top civil servant at the Treasury, Tom Scholar, who had plenty of experience and wise counsel to offer.

She and Kwasi Kwarteng refused to enlist the support of the Office for Budget Responsibility – a body introduced by her own Conservative Party – to provide greater reassurance to the markets. In a headstrong and frankly rather childish manner, she presumed she could reject the advice of experts and face down the massed forces of international capital. She was wrong.

Scapegoating is poor strategy

To sack Kwarteng as chancellor (even though she co-authored and advocated his policies) may be business as usual as far as politics is concerned. But it is not the act of a leader who should expect to be trusted or respected. There was a sense, during her limp and inadequate press conference that followed the firing, that perhaps Truss herself was beginning to recognise that she was falling badly short of what is needed in her role.

It will be for psychologists or close friends, rather than students of leadership like myself, to explain why Truss has had so much difficulty grasping the reality of the situation which confronted her. She has now, perhaps, finally started to see how much more difficult it all was than she imagined. But it is far, far too late.

Leadership should not be an ego trip or seen as some sort of game. It is not a playground for ideological experiment. It is about making a contribution, and leaving your organisation better placed to face the future. Leadership, finally, is not about you, it is about everybody else. I fear Liz Truss did not understand very much of this at all, and it will now cost her both her job and her political career.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.