Ukraine is Turning Advertising into a Weapon of War

When a preview of Vogue’s October cover story on Ukrainian first lady Olena Zelenska hit Twitter on July 26, reactions on social media were swift and polarized. Some critics said that a photo shoot by famed photographer Annie Leibovitz for a fashion magazine was a “bad idea” and glamorized war.

Others lauded the magazine and Ukraine’s first lady for bringing awareness to the suffering of Ukrainians, five months after Russia first invaded its neighboring country.

In the cover photo, the 44-year-old Zelenska is photographed wearing a cream-colored blouse with rolled-up sleeves, black trousers, and flats. She sits on the stairs of the Ukrainian Parliament, leaning forward with hands intertwined between her knees. Her makeup is minimal, her hair casually tossed as she looks directly at the camera. Within hours Ukrainian women started using the hashtag #sitlikeagirl to share photos of themselves in the same pose as a show of solidarity.

Vogue’s profile of Zelenska, headlined “A Portrait of Bravery” and written by journalist Rachel Donadio, fits into a larger communication strategy, mounted by Ukraine’s government, that’s intended to keep the world focused on the country’s fight against Russian aggression. As part of that effort, Ukraine also initiated a nation branding campaign in April with the tagline “Bravery. To be Ukraine.”

As a communications scholar, I have studied how former communist countries like Ukraine have used marketing strategies to burnish their international reputations over the past two decades – a practice known as nation branding.

Ukraine, however, is the first country to launch an official nation branding campaign in the midst of war. For the first time, brand communication is a key part of a country’s response to a military invasion.

“We have no doubt we will prevail.” As the war in Ukraine enters a critical new phase, the country’s First Lady, Olena Zelenska, has become a key player—a frontline diplomat and the face of her nation’s emotional toll. https://t.co/DCXWYnzAsK pic.twitter.com/wcaY5IFGHf

— Vogue Magazine (@voguemagazine) July 26, 2022

Nation branding and the end of communism

The idea that nations can be branded emerged at the beginning of the 21st century. This kind of work uses advertising, public relations, and marketing techniques to boost countries’ international reputations. Campaigns are often timed to coincide with major sporting, cultural or political events – like the Olympics.

After the fall of the Berlin Wall and the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, formerly communist Eastern European countries were particularly eager to rebrand themselves and get an updated international image.

When Estonian musicians won Eurovision in 2001, Estonia became the first post-Soviet country to hold this prize. Subsequently, the country’s government hired an international advertising company to design a modern national brand for Estonia as it prepared to host Eurovision the following year.

Research has shown, however, that former communist countries’ nation branding efforts were not meant just for international consumption. They also provided a new way to talk about national identities at home, and re-imagine national values and goals, via marketing terms.

But until 2022, no country had used nation branding to fight a war.

‘Bravery is our brand’

Executives from the Ukrainian advertising agency Banda first pitched the idea for Ukraine’s Bravery Campaign to the government shortly after Russia invaded in February. Based in Kyiv and Los Angeles, the agency had already worked before the war on government-sponsored campaigns, marketing Ukraine as a tourism and investment destination.

Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky endorsed the wartime branding campaign and publicly announced its launch on April 7, in a video address. “Bravery is our brand,” he stated. “This is what it means to be us. To be Ukrainians. To be brave.”

In the following months, Banda produced numerous messages in formats ranging from billboards, posters, and online videos, to social media posts, T-shirts, and stickers. A campaign website offers downloadable logos and photographs and asks visitors to share the message of bravery and donate to Ukraine.

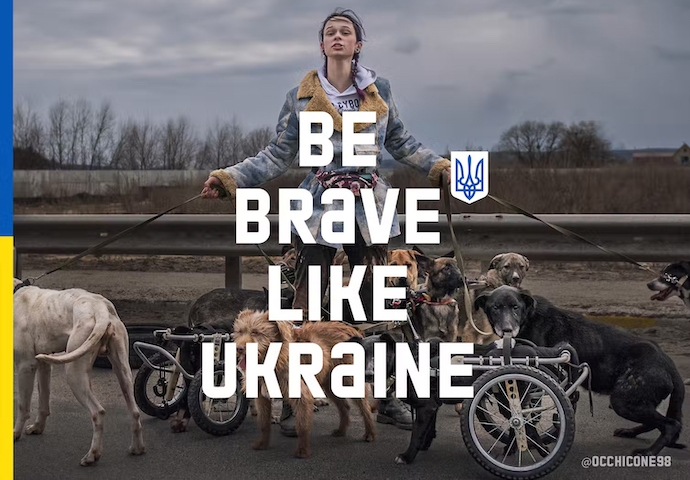

Some billboards feature images of courageous, ordinary Ukrainians and soldiers. Other billboards are emblazoned with bold slogans in the blue and yellow colors of the Ukrainian flag. They urge audiences to “Be brave like Ukraine” and say that “Bravery lives forever.”

Inside Ukraine, the campaign’s messages appear on everything from juice bottles to 500 billboards in 21 cities. The campaign is also running in the U.S., the United Kingdom, Canada, and 17 countries in Europe, including Germany, Spain, and Sweden, according to AdAge.

This massive communication effort is happening at a minimal cost to Ukraine. Banda is donating its services, and the Ukrainian government pays only for production costs. Media space, including high-profile billboards in Times Square and other major cities, was donated by several global media companies.

Branding as a weapon of war

Banda’s co-founder, Pavel Vrzheshch, has said the campaign aims to strengthen Ukrainians’ morale as they continue to fight Russia. But the focus on bravery is also about Ukraine’s future, he says.

“The whole world admires the Ukrainian bravery now, we must consolidate this notion and have it represent Ukraine forever,” Vrzheshch said in a media interview.

At its core, the campaign attempts to transform an intangible value, like bravery, into an asset that can be converted into real military, economic and moral support. In other words, it aims to cultivate positive public opinion in the West that will support further aid to Ukraine in order to help fight the war.

This way of using brand communication in a war is unprecedented in at least three ways.

First, rather than relying only on diplomatic channels to seek international support, Ukraine is harnessing popular media and social media networks to speak directly to citizens of other countries. It gives ordinary people around the world a chance to show solidarity through donations or by sharing campaign messages and pressuring their government to support Ukraine.

A formal brand campaign also allows Ukraine to extend the visibility of the war beyond news coverage. As the conflict continues, it is likely to fade from news headlines in international media. But billboards, social media posts, and the strategic use of entertainment publications like Vogue can keep it in front of audiences.

Finally, the best brand messages connect with consumers by inviting them to imagine better versions of themselves. Famous ad slogans like Nike’s “Just do it” or Apple’s “Think different” illustrate this idea. So does Ukraine’s call to people around the world to “Be brave like Ukraine.”

It is notoriously difficult to measure the effectiveness of nation branding campaigns, as brand consultants point out. The process is costly and time-consuming, and results are often contested.

The direct impact of the Brave Campaign may not be clear for months to come. It is also not clear how long its message will continue to resonate. But it is clear that Ukraine is transforming nation branding into a new propaganda weapon, adapted for the age of consumer culture and constant media stimulation.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.