What Syria is Teaching the West

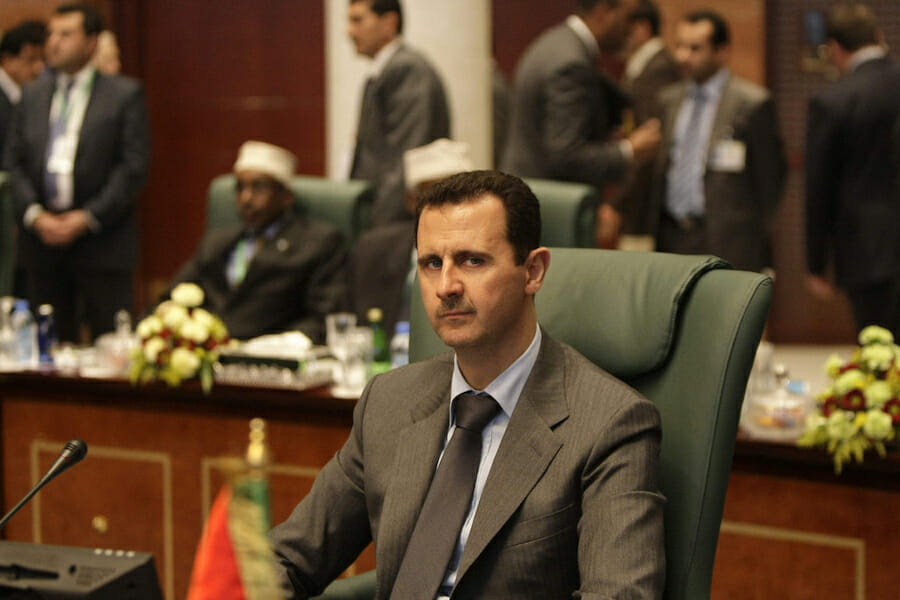

It should come as little surprise to anyone that the fragile cease-fire in Syria has failed and is evidence that, contrary to what many pundits contend, the tide continues to be on Mr. Assad’s side, given the time that has passed, the fractured nature of the opposition, and the bungled manner in which the West has addressed the subject. As Syria demonstrates, with each passing month the Arab Awakening evolves in new and unexpected ways. The question is whether the West is evolving along with the Awakening, or will remain stuck in a unidimensional view of MENA.

As pressure mounts on foreign powers to consider intervening militarily in Syria, analogies are naturally being drawn between what NATO accomplished in Libya and whether something comparable may be possible in Syria. Military intervention would perhaps make the West feel better — knowing that it attempted to do something concrete to end the bloodshed — but it is unlikely to be successful for several reasons. An air and sea campaign against Syria would likely prove more difficult than in Libya.

The Syrian military, which numbers more than 500,000 men (including reservists), is more formidable than Gadhafi’s forces and would prove more challenging to impact by air. Syria possesses more than 10,000 armored fighting vehicles, 4,000 surface-to-air missile launchers, and a formidable array of anti-aircraft systems.

Moreover, unlike in Libya, the Free Syria Army (FSA) has not established territorial control over any discernible part of the country, which makes it very difficult to imagine defending any positions. Any military campaign would likely result in numerous instances of mistaken identity and civilian casualties, so what would a military campaign be supporting at this time?

As an alternative to an air and sea campaign, some have advocated funneling arms to the FSA, but this too has dangers — the most obvious of which is that it could lead to blowback, just as was the case in Afghanistan. This is particularly worrisome because there are now reports that Al-Qaeda is playing a significant role against Mr. Assad. Another danger is that there is little reliable information on the FSA, or how much control it exerts over its subordinate units. As a result, there is no guarantee that weapons would not be channeled to terrorists, criminals, sectarians, and other unsavory groups.

Indeed, there is considerable fear that the fall of the Assad regime could lead to a period of sectarian bloodletting similar to that of Iraq, following the U.S. invasion in 2003. Are Europe and Syria’s neighbors prepared for that? Would it be smart to induce that at a time when a conflict between Israel and Iran appears imminent? Some observers believe that it is foolhardy for the U.S. to consider engaging itself in the Syrian uprising in any way. To date the Arab Awakening has delivered far less than hoped, has not generated a single liberal Arab democracy, and has produced far more radical pro-Islamic governments and political movements than the West anticipated, or wanted. On the contrary, the changes of government in North Africa over the past year have empowered political Islamists who have no loyalty to democratic governance, and are already playing games with political history.

The truth is that military intervention by the West is highly unlikely to result in a satisfactory conclusion. The likelier result is that it will be sucked into a long-term conflict for which there is no exit plan — which was indeed a concern in Libya, as well. There is no reason to even consider a “no-fly” zone in Syria at the present time, as the Syrian air force has not to date been involved in the conflict. Moreover, Syrian troops have largely been loyal to Mr. Assad, and at this point in time, it does not appear reasonable to assume that the tide may shift in due course. If that were going to occur, it would presumably have occurred already.

Unlike in Libya, the major powers are not in unison about what to do. Part of the reason for this is that they have seen the net result of the Libyan assault — which remains a question mark. Lawlessness and the absence of security have been the result, and it is more likely than not that yet another pro-Islamist regime will be born once elections occur in Libya. Unlike in Libya, the geopolitical dynamics are very different. Syria is a client state of Russia and will be able to continue to rely on its military and diplomatic support.

Russia continues to support Mr. Assad militarily and politically, and China and Russia both vetoed the UN resolution condemning human rights violations in Syria. China sees the need to stress the dangers of intervention and “state making” by the West, given its obvious limitations. Surely, the West knows by now it cannot simply wave a magic wand and expect everything to fall into place. Experience shows that decisions made when a humanitarian crisis is developing are usually driven by emotion, the press, and popular sentiment. Starry-eyed notions of what “can be” are just that. What is needed now is a good dose of realism and caution. The stakes are higher than ever before. There may come a time when the West may feel it has no choice but to intervene militarily in Syria — but now is not that time.

The global community is firmly against the continuation of the Assad regime, reasoning that Assad must go by virtue of his family’s long dictatorial rule, its alliance with Iran, and its crackdown against demonstrators. In a perfect world, they may well be right, but that this is simplistic and short-sighted. As reprehensible as many Syrians and others may find Mr. Assad, they fail to imagine what Syria and the region may be like in his absence.

Given that all three of the countries that have so far experienced a change of government in northern Africa have either already elected conservative Islamist governments, or are poised to do so, is there any reason to believe that if more governments in the region fell, the result would be any different? Did Saleh’s departure in Yemen result in a liberal democracy? Given the strength of the Islamist movement in Algeria, and Bouteflika’s support of the Gaddafi regime until its last day, can the electoral outcome of an overthrow of his government be in serious question? Is there any reason to believe that a radical Islamist regime wouldn’t, in the end, be the result of Mr. Assad’s departure?

Turkey has led the charge against Mr. Assad but appears not to have considered the possibility that a more radical regime may ultimately emerge in Syria. Should a radical government take over in Syria, Israel, which is already in its most precarious position since the 1967 War, would be virtually surrounded by Islamist governments. The only missing piece would be Jordan. Given this, the likelihood that Israel will feel it has no choice but to attack Iran’s nuclear program this year has surely risen. What would it be giving up by doing so, after all? Israel argues that it faces an existential threat from a possible nuclear attack by Iran — but it also faces a possible existential threat as a result of the new landscape taking shape around it. For that reason, the Israeli government surely prefers that Mr. Assad stay right where he is.

And I would argue that is exactly what the West should prefer, for it should now be apparent to all that rapid political change is not necessarily a good thing, and the results of that change in the region to date are not encouraging. As much as the West would like to believe that everyone in the world prefers western-style democracies, that is not, in fact, the case. Democratic elections often deliver results contrary to what the West would like to see.

Many throughout the world look at what American democracy has descended to – with big money dominating the political process, wealthy and powerful people who break the law not spending a day in jail, and some people who object to the status quo being labeled threats to national security – and wonder why they would want to emulate it. In addition, it would be nice if the world were simply a place where demonstrators demonstrate, dictators fall, and liberal democracies take their place — but that is not the world we live in. As Mr. Assad has said, the West should be very careful what it wishes for in Syria, because it is unlikely to get what it wants.