Who Votes for a Mayor like Rob Ford?

Toronto politics has never been the stuff of international headlines. A prosperous and cosmopolitan metropolis that has attracted a million new residents every decade since the end of World War Two, Toronto’s quiet virtue has been an honest, uncontroversial, and competent government.

But, as any connoisseurs of Twitter or late-night comedy television will tell you, all that has changed. After police surveillance revealed his friendly relations with known drug dealers and his public admission of having smoked crack cocaine while in “one of my drunken stupors,” Mayor Rob Ford has finally put Toronto on the map in a way that countless tourism promotions and investment development campaigns have never managed.

Questions abound: who exactly is Rob Ford? How did he get elected in the first place? What may enable him to hang onto office, and possibly be re-elected, when lesser scandals have felled much mightier politicians?

These questions are closely linked through Rob Ford’s singular appeal to an important and under-appreciated segment of Toronto’s electorate.

To understand Toronto’s current political quagmire, we must separate Rob Ford the man from what he represents in political terms. Ford’s personal foibles – his fondness for junk food, episodes of public drunkenness, erratic and confrontational behaviour and verbal gaffes – were well documented during the 2010 election campaign.

Now it appears that at least some of this behaviour may stem from substance abuse. If, as is alleged, Ford suffers from drug and alcohol addiction, this should be viewed as a personal tragedy. Whether or not his personal life disqualifies him from office will be up to the electorate. There are no legal means of removing a sitting mayor unless he or she has been convicted of a crime – and Ford has pledged to run again.

But setting aside his personal travails, it is clear Ford represents a style of back-to-basics populism that resonates with a particular type of voter. His dark horse candidacy in the 2010 election was regarded as a joke by the downtown cognoscenti until polls put him in the lead. Ultimately, he won with 47% of the vote, 12 points ahead of the establishment candidate, former provincial deputy premier, and downtown condo-dweller George Smitherman.

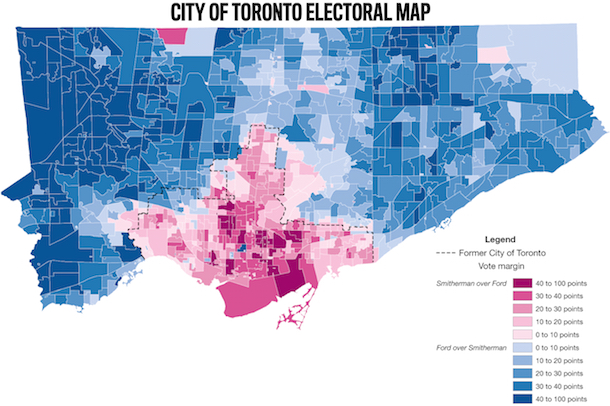

My analysis of the electoral data shows 80% of Ford’s votes came from the postwar suburban zone. Few parts of the city were competitive. Only 16% of polling divisions (180 out of 1110) had an the electoral margin between Ford and Smitherman less than 10%. A map of the election results reveals a stark city-suburb divide. Having captured suburban voters so completely, Ford won simply because there are more votes to be had in those areas. About 71% of eligible voters live in the suburbs.

A similar divide was visible in prior elections. In 1997, suburban Mel Lastman trounced downtowner Barbara Hall. In 2003, downtowner David Miller prevailed, but only by racking up large vote surpluses in core areas and making inroads in middle-ring suburbs. (The 2000 and 2006 elections were lopsided affairs in which incumbent mayors faced weak challengers.)

The city-suburb electoral divide is durable and has both political and social causes. Politically, we can view it as an outcome of 1997 amalgamation of the former City of Toronto with five suburban municipalities. City and suburban residents tend to have different expectations of what local government should do.

The old city, with 750,000 residents, exemplified what political scientist Clarence Stone refers to as a “middle-class progressive regime” — a cosy, neighbourhood-oriented politics in which the wealthy commercial tax base subsidised generous services to residents. The postwar suburbs exemplified a leaner mode of governance focused on providing low-cost services to individuals as householders and drivers. This fundamental difference of perspective on the role of local government remains unreconciled.

The story also has a socio-economic dimension. Toronto’s middle-class suburbs have suffered as low-wage service jobs have displaced the old manufacturing base. At the same time, the rapidly gentrifying core is increasingly a playground for theorist Richard Florida’s “creative class.” My hunch is that many less-well-off suburbanites see the downtown condo boom and other benefits of Toronto’s postindustrial transformation flowing to the core at their expense.

Squeezed in the jaws of rising income inequality, many suburbanites were receptive to Rob Ford’s simple and coherent message: cut waste in government, hold the line on taxes, and end the “war on the car.” For them, Ford was the right man at the right time.

Ford may yet be sunk by his personal problems, but the underlying division on which he capitalised — and which forms the basis of his personal appeal — endures. In the meantime, Toronto’s many policy challenges, so demanding of creative leadership, remain unanswered.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.