Tech

Justice Thomas Fires a Warning Shot Across Big Tech’s Bow

In what was expected to be a routine dismissal of the Biden v. Knight First Amendment Institute case, Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas wrote a concurrence that put the major tech companies on notice. Concerned about what he sees as the unprecedented “concentrated control of so much speech in the hands of a few private parties,” Thomas provided a legal roadmap for how to put restrictions on these dominant digital platforms that control so much of our information infrastructure.

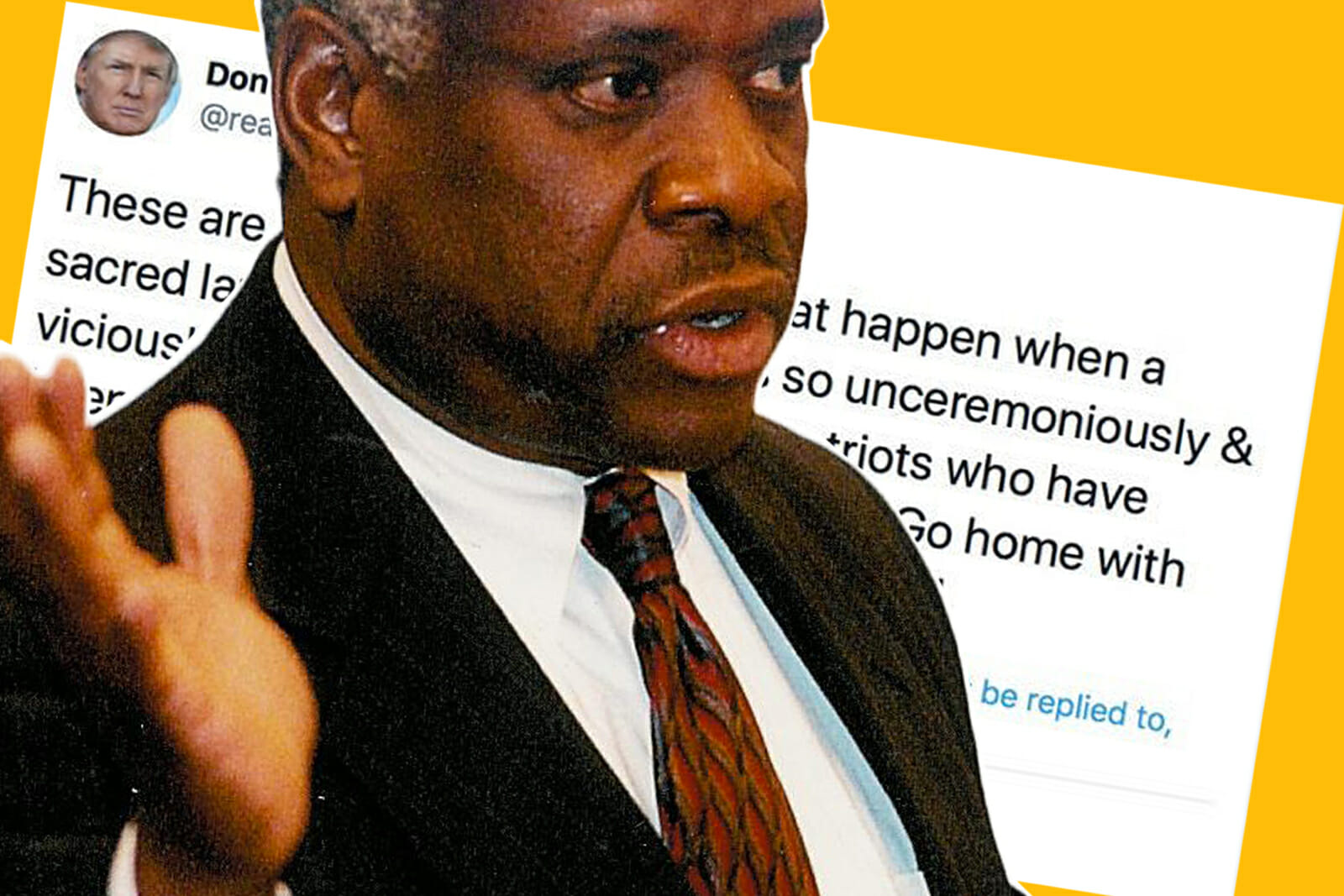

This case started when former President Trump was sued by several Twitter users that were blocked from interacting with his account. Both the District Court and, on appeal, the Second Circuit, held that Trump’s account was equivalent to a public forum and that it was a violation of their First Amendment rights to restrict people’s access to the comment threads. By the time the case made it to the Supreme Court, however, Donald Trump’s loss in November made the case moot; there was no longer any legal controversy because Trump was no longer president. This didn’t stop Justice Thomas from taking the opportunity to rethink how the law should treat digital platforms.

Justice Thomas started by explaining why he did not think Trump’s Twitter account was a public forum. Although Trump used his Twitter account in his capacity as a public official and it was open to the public for expressive activity, both common characteristics of a public forum, it was not truly under Trump’s control. This was made clear when Twitter began censoring and then, finally, suspending his account. Because Twitter maintained ultimate control over the account, Justice Thomas suggests that it cannot legally be considered a public forum.

But even if Twitter would not currently be considered a public forum, that does not mean it will never be treated as such. Justice Thomas lays out two legal doctrines that might be used to allow the government to exercise more control over Twitter and other digital platforms: common carrier doctrine and public accommodation doctrine. Under both, a company so designated must “serve all comers” without discrimination. Some commentators have already raised the concern that such a requirement might violate the companies own First Amendment rights. To compensate for this burden, however, the government often provides benefits, such as “immunity from certain types of suits.”

Traditionally, common carriers are businesses in the transportation and communication industries. Digital platforms have many similarities with these industries. First, they are essentially communication networks that “carry” information between users. Second, many of these digital platforms have dominant market positions. Although none are absolute monopolies, there are no reasonable alternatives. As Justice Thomas put it, “A person always could choose to avoid the toll bridge or train and instead swim the Charles River or hike the Oregon Trail.” This market power further justifies regulating these digital platforms as common carriers. In addition to Twitter, Justice Thomas specifically calls out Facebook, Google, and Amazon as tech companies that are capable of manipulating the availability of, or outright silencing, different viewpoints on a massive scale.

Similar to common carriers, a public accommodation refers to a related, but more broadly defined, group of businesses. It includes any companies that “hold themselves out to the public but do not ‘carry’ freight, passengers, or communications.” Hotels and restaurants are the archetypal examples. Although there is some disagreement among courts about whether a public accommodation must be a physical space, Justice Thomas states that “digital platforms bear a resemblance to that definition” because they provide services to the public. He sees this as another potential legal means to exercise control over tech companies.

This concurrence can be seen as an invitation to Congress to pass legislation limiting Big Tech’s ability to censor users. In his conclusion, he makes it explicit, stating that legislation relying on the common carrier and public accommodation doctrines “may give legislators strong arguments for similarly regulating digital platforms” (emphasis added). He is essentially saying that the Court will look favorably on any laws that treat Big Tech as common carriers or public accommodation that must serve all comers. Justice Thomas suggests that, because Congress has already given immunity from suit under Section 230, it should impose “corresponding responsibilities, like nondiscrimination.” Republican Senator Josh Hawley’s now dormant Ending Support for Internet Censorship Act is probably closest to what Justice Thomas envisions. It would have denied Section 230 immunity to any company that did not maintain “political neutrality in content moderation.”

Importantly, Justice Thomas was not able to get any of the other Justices to join in his concurrence, suggesting that the larger Court may not share his views on this. Regardless of whether the law will evolve in the way that Justice Thomas is offering, however, he was certainly correct about one thing. The legal system “will soon have no choice but to address how our legal doctrines apply to highly concentrated, privately owned information infrastructure such as digital platforms.”