Books

Q&A with Roots of Peace founder Heidi Kuhn

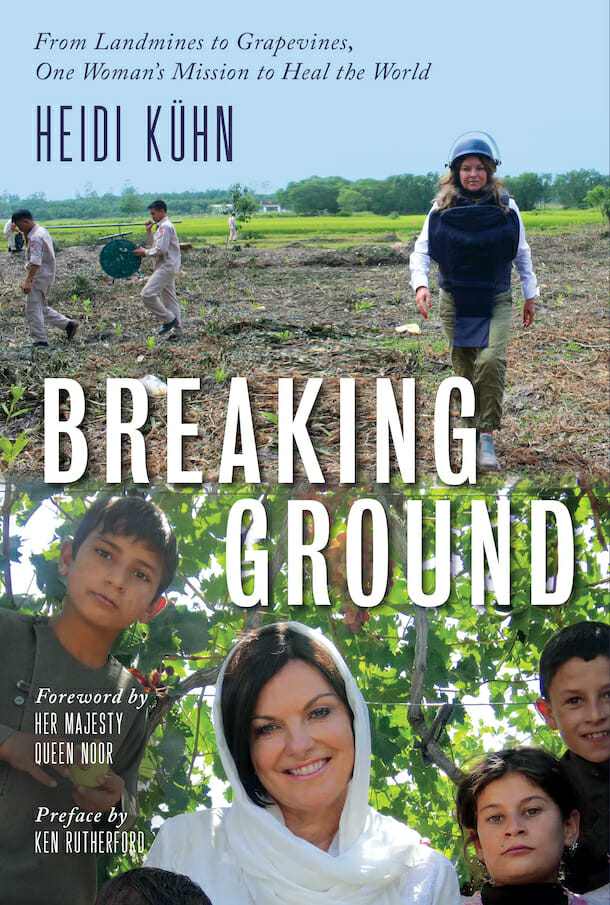

I found your book Breaking Ground: From Landmines to Grapevines, One Woman’s Mission to Heal the World to be really engaging. What inspired you to write it?

I wrote Breaking Ground to inspire others to pursue their dreams for peace.

If a mother from Marin County may start a concept from the basement of her home and catapult the idea to the 38th floor of the United Nations, just imagine what we can all do together with positive intentions to build a better world!

Many California dreamers started their idea in the ‘Garage.’ As a woman, I had to go subterranean and overcome many obstacles to get myself out of the ‘Basement.’

Yet, with tenacity and courage to overcome daunting hurdles, I was able to address one of the world’s most challenging obstacles—landmines sown into the skin of Mother Nature.

Over 23 years after the Ottawa Treaty to Ban Landmines was signed, there still remains millions of landmines and unexploded ordnance remaining dormant in the ground. As a Croatian farmer once told me, they are “ghosts in the ground” preventing the cultivation of a field. The land is held hostage by landmines, and we must remove these seeds of terror from the soil, soul and minds of global citizens who live on war-torn lands. The economics of peace is only possible when the land is cleared from explosive remnants of war. Today, there are an estimated 60 million landmines silently poised in over 60 countries. Over two decades later, these silent killers remain hidden in the soil awaiting the innocent footstep of a child or the shovel of a farmer to detonate.

Many friends believe that the landmine situation was solved after the death of the late Princess Diana. Hollywood gathered in support of the eradication of landmines through the leadership of Sir Paul McCartney and his former wife Heather Mills McCartney. But, after their separation, the issue of landmine dissipated from the forefront of the international agenda. People believe that landmines are gone, since they are not in the frontpage of the news anymore. However, each day, landmines silently maim and kill innocent footsteps.

I decided to write Breaking Ground to show the global community that our footsteps for peace truly make a difference. In a world which is jaded by doubts that peace is possible, Roots of Peace has taken bold footsteps for peace with a consortium of stakeholders from a cross-section of society—California vintners to Chevron; pennies from children to USAID funding.

I remain most grateful to Her Majesty Queen Noor for writing the Interfaith Forward to my book. And, my deepest gratitude to Dr. Ken Rutherford who escorted the late Princess Diana through Bosnia-Herzegovina only three weeks prior to her tragic death–writing the Preface to Breaking Ground as he describes his own pain in losing both legs to the perils of a landmine.

Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-CA) and Cindy McCain wrote inspirational words on the cover—which transcend politics, and highlight the impact of landmines on innocent children.

The opening of the book begins with my Granny McNear’s favorite quote: “Coincidence is a miracle in which God prefers to remain anonymous.” As the book prepares to launch, we are faced with the challenge of a Spring planting season where there is not only the phantom of hidden landmines in the soil, but the invisible pandemic of the COVID-19 virus. Afghan farmers live in fear where to plow their fields, as they avoid the perils of landmines. Now, the health of our Afghan farmers are further at risk with the rapid spread of the coronavirus.

Breaking Ground is a timely book, as we must come together as global citizens to face the challenges of hidden landmines and viruses which know no borders. As we heal the soil, we heal the soul.

Many young people under the age of 30 years old were elementary school children when the 9/11 attacks occurred in the United States. They have grown up disillusioned that we live in a war-torn society where conflict continues to unfold with no solutions. Breaking Ground is an honest story of the journey of a mother to heal the wounds of war and plant the roots of peace for future generations to thrive. It is a story of grounded vision and hope.

Conflicts in places like the Balkans and in other hot spots have ended but new conflicts seem to arise to take their place fairly frequently. How has the mission of your organization, Roots of Peace, evolved over time?

Roots of Peace began our work in the Balkans in January 2000, the first month of the new millennium. When I took my first footsteps into a minefield, there were an estimated 1.2 million landmines in Croatia. Our business model to DEMINE-REPLANT-REBUlLD has provided a unique business model resulting in the economics of peace. Two decades later, Croatia is among the top tourist destinations in the world.

Our Roots of Peace business model has been replicated in Afghanistan, as we have cleared over 100,000 landmines in the Shomali Plains north of Kabul since the September 11th attacks with funds provided by Diane Disney Miller, daughter of Walt Disney, owner, Silverado Vineyards in Napa Valley. In 2004, we introduced trellis grapevines which greatly increased the income for Afghan farmers to grow high-value crops. For instance, the average Afghan farmers who grow wheat will earn $800 per month, $1,200 growing poppies, and over $4,000 growing fresh trellis grapes and pomegranates. Furthermore, we have provided exports to new markets in India and the UAE. In 2014, Afghan agricultural exports averaged $250 million. In 2020, the agricultural exports exceeded $1.4 billion due to the work of Roots of Peace funded by USAID. Together, we made history for peace.

What are the main challenges your organization faces around the globe as it tries to carry out its mission?

On March 28, 2014, Roots of Peace was attacked by the Taliban in a four-hour gun battle.

Explosives were detonated at our front door, as the insurgents targeted a kindergarten daycare center adjacent to our offices. The Afghan guards bravely fought off the terrorist, as they protected an American NGO from harm. The military had never heard of such a situation, as most Afghan guards would flee. It was due to our respect for the Afghan farmers and families, that the guards protected our mission from harm.

While this was a defining moment for our organization, I decided to lead with faith—not fear.

Roots of Peace also faces funding challenges. It costs approximately $3 to put in a landmine, and over $1000 to remove. The land must be cleared ‘inch by inch’ and then returned to farmers for cultivation. Since we are so fortunate not to have landmines in the United States, many are not willing to fund a global challenge which is not in their backyard. This is why my new book Breaking Ground will hopefully raise both awareness and funds to remove the scourge of landmines. It is also an important time to invest in development.

The U.S.-Taliban peace negotiations were successfully signed earlier this year. But, once the ink has dried on the treaty, the hard work must be done by empowering the farmers with agricultural roots to succeed. The Spring planting season in March must be greeted with shovels, not swords. Afghanistan is a country which is 80% dependent upon agriculture.

The young Afghans living in remote regions must be empowered with modern farming techniques, so that a harvest of hope may be cultivated. If we wait for months of logistical roadblocks and political landmines, we are at risk of missing this important planting season. Truly, it is a time to turn ‘swords into plowshares’ as we invest in the Roots of Peace

My father was a Peace Corps volunteer in Ethiopia in the early 1960s. He often speaks about the challenges in teaching agricultural best practices. One particular challenge was ensuring that his students didn’t revert back to old practices once he left. Is this a challenge that your organization faces?

Your father is a wise man. The decades of war in Afghanistan has broken the age-old cycle of planting that was passed on from grandfather to father to son. War broke the value chain.

When we arrived in Afghanistan in 2003, grapes were grown on mounds and at risk to disease and poisonous snakes which lurked beneath the rotting leaves. Farmers would harvest in the heat at mid-day and hope to make a meager profit as they dragged their produce to local markets.

Roots of Peace seeks to restore the value chain. With our ‘train the trainer’ technique, we are teaching local farmers best practices to share with their neighbors. With funding from USAID, we introduced cold storage facilities, and trained the farmers to pack the fruits in corrugated boxes in sanitary conditions. The fruits were labeled AFGHAN FRUITS to be branded for local markets, and the local farmers witnessed their incomes rise dramatically.

As we bring Afghan traders to new markets in Delhi and Dubai, we introduce them to supermarket buyers who are thrilled to welcome the ‘Kabuli Walas’ back to their shelves. This was a beloved term which was recognized by their grandfathers, as the Afghan fruit was considered among the best quality in the region. As we make these market linkages, we are restoring the value chain for the farmers to stand on their own two feet—without the fear of landmines beneath their plow.

Can you discuss how Roots of Peace is incorporating the challenge of climate change into its work once an area is cleared of mines and farmers can start planting crops?

Smallholder farmers are among the most vulnerable populations to climate change. As most crops grow under a narrow set of conditions, many crops beginning to move their production zones. As part of our work, we commit significant time in the project planning phase where we identify the proper crops that can both grow in a given climate and can find strong markets for them to be sold. Sometimes this means traditional crops grown in a given region but often cases, due to climate change, regions need to begin the transition to alternative crops. We have a farm establishment model where we pride ourselves on being able to create sustainable, practical training that adapts to local context. This allows farmers to adapt to the direct issues they face from climate change. To reduce the causes of climate change we support efficient production systems that make the best use of resources available while still producing the level of quality that is required for their target markets of the farmers’ crops.

The Trump administration is embracing landmines, reversing Obama era policies on their prohibition. How problematic is this?

Roots of Peace is a humanitarian, non-political and interfaith organization.

However, in December 1997, I invited three California vintners (Mondavi, Beringer, and Wente) to join me in Canada to witness the historical Ottawa Treaty to Ban Landmines.

Today, there are 164 state parties to the treaty. The U.S. was not a signatory and still has not signed the ban. Our delegation attended as farmers respecting the plight of other farmers.

This was a powerful message, as we inspire others to be stewards of the earth we share.

Earlier this year, the U.S. and the Taliban signed a historic agreement for bringing peace to Afghanistan. After 18 years of war, the agreement stands to bring American troops home within 14 months. The deal also paves the way for talks between Afghans to end one of the world’s longest-running conflicts. Yet, when landmines are planted, this creates a paradox.

When we first arrived in Afghanistan in 2002, we met farming populations whose harvests were crippled by the threat of landmines detonating beneath their feet, and got to work demining them. Where we were successful, or where the landmine threat was less prevalent, we saw agricultural yields hamstrung by antiquated techniques. Afghanistan is the most heavily mined country in the world, and the concept of planting additional landmines only makes our work more complicated as we dig deeper for sustainable peace.

Are there some areas of the world that were particularly challenging? Conversely, are there projects that Roots of Peace has completed that you’re particularly proud of?

The Vietnam War ended on April 30, 1975. Yet, nearly 45 years later, these explosive remnants of war remain buried in the ground long after the guns have silenced. Since the war ended, over 100,000 innocent Vietnamese footsteps have been maimed or killed by these explosive legacies of war.

During the Vietnam War, more bombs were dropped in Quang Tri province, former DMZ, than in World War I and II combined. Today, over 80 percent of the land remains contaminated by these landmines/UXO and cluster munition. When I was a student at U.C. Berkeley during the 1970s, my fellow classmates were dedicated towards the peace movement. Yet, there is no ‘peace’ when we close our eyes to this legacy of war and pretend that life has gone on as usual for the innocent. I often wonder how we may be so blind as adults.

In 2010, Roots of Peace began our work in Quang Tri province. My own son, Tucker Kuhn, age 25, was on the frontline for peace as our Country Director. Blond, blue-eyed, he would have been sent to Vietnam with a DRAFT card during my generation. Now, he was drafting peace.

For the past decade, Roots of Peace has partnered with MAG (Mines Advisory Group) and raised over $500,000 to hire all-women deminers who bravely work tireless hours to remove these explosive remnants of war for the sake of their children. They are on the frontline for peace.

Today, our Roots of Peace Country Director today is a woman, Ms. Vo Thi Lien. She is the daughter of a farmer, and has gone forth to train over 3,000 Vietnamese farmers to grow fresh black pepper on former battlefields. Together as women, we have worked with determination to export fresh black pepper to be sold in new markets in California. Morton and Bassett Spice Company is now selling this black pepper on supermarket shelves featuring our Roots of Peace logo. Morton Gothelf, CEO, served as a pilot in the Vietnam War during the 1960s and this is his way of giving back. The land is hot with black pepper, not landmines!

Together, we have turned MINES TO VINES—planting black pepper vines on former battlefields.

This act of peace makes this grandmother very proud!

There are millions of landmines in Afghanistan. How optimistic are you in the face of a new peace agreement that your organization and others can accomplish a landmine free Afghanistan?

On January 31sst, the Trump administration—in a Friday afternoon news drop—announced that it was expanding the use of landmines in battle. The Obama-era ban on the use of landmines outside of the Korean Peninsula inhibited the president’s “steadfast commitment to ensuring our forces are able to defend against any and all threats,” the administration stated.

While the story did garner fleeting national attention, it was predictably churned into the news cycle and has all but disappeared from the headlines.

Renewed deployment of landmines will dramatically undermine U.S. peacekeeping efforts by placing a burden of fear and violence on civilian populations. Opposing military forces benefit from access to detection technologies that civilian populations lack. There are an estimated 60 million landmines in 60 countries that maim and kill innocent farmers long after the guns have silenced. Today, over 70 percent of landmine victims worldwide are civilians. Over half of those are children.

I have seen the way landmines paralyze civilian efforts in times of war and tunes of peace alike.

Roots of Peace’s vision of transforming mines to vines—replacing the scourge of landmines with bountiful vineyards and orchards in Afghanistan—is based upon the belief that landmines are not simply tools of war. They are perpetrators of war. They make sustainable peace impossible, long after the conflicts that put them in the ground have ended. Landmines carry no flag, and know no color, and we will continue our humanitarian effort to plant the roots of peace for future generations to thrive—despite the political landmines.

What will it take for the world to be landmine free?

If we put our minds and our resources to this effort, we may remove all landmines in my lifetime. This is an effort worth pursuing!

My business plan is to put myself ‘out of business!’ I envision a world without landmines, and where farmers are trained to plant agricultural crops with access to new markets.

Together, may we plant the Roots of Peace for future generations to thrive.

Post-conflict regions are often forgotten once a peace agreement is signed or a particular side is defeated leaving in place a land that is scarred and littered with landmines. Can you discuss the challenges of keeping people’s attention focused on countries that the world would prefer to forget?

Wars have a draining affect not only on every aspect of society for a war-torn land, but for outsiders as well. In a country such as Afghanistan where there is much fatigue amongst the U.S. population for our 18+ year war, there is a strong sentiment to put an end to our presence there. We have seen the effects of a hasty post-peace agreement withdrawal as evidenced by the instability in Afghanistan after the withdrawal of Soviet forces in the 80s and how the country became a hotbed for international terrorism. What we are now focusing on is showing the impact of our work at the community level and how peace is a much more complicated process. We are currently developing indicators such as measuring if areas with higher levels of ROP activity appear more socially integrated and with fewer conflicts between new arrivals or families who had left the area.

Early results have been very positive. Similarly, areas with higher levels of RoP programming appear more likely to resolve conflicts within the community. As we develop a better understanding that is backed up with data, we hope to provide a roadmap to a more comprehensive plan to what true peace is within a community, not just defining peace as when guns fall silent.