Sinn Féin has a Challenge and it’s Gerry Adams

While the world watches the fascinating and increasingly bizarre election season in the United States this year, another country has just emerged from a bruising and monumental general election. On Friday February 26th the people of Ireland flocked to their local primary schools, town halls, and gymnasiums to vote on their next Dáil (Parliament).

Unlike countries with majoritarian or two-party systems, the Irish have a realistic choice among four major parties, five or six smaller parties, and an array of independents. The ruling coalition between Fine Gael (Tribe of the Irish) and Labour has held power for five years. Facing off against them are Fianna Fail (Warriors of Destiny) and Sinn Féin (We Ourselves). The next Dáil is expected to be made up of seven or eight parties and a lot of non-aligned independents. The next government will be comprised of either a party with a clear majority, or a coalition. While the latter is anticipated; the question is whether Sinn Féin will be part of it.

Vote counting continues as of Tuesday 1st March and whatever the outcome, a minority government seems likely.

2016 is also significant on the Irish calendar because it marks the centenary of the Easter Rising of April 1916. The event triggered the beginning of the Irish War of Independence and was largely blamed at the time on Sinn Féin.

It’s a legacy that the modern party is only too happy to embrace, as is almost every nationalist or republican group in the country. In reality, Sinn Féin had little or nothing to do with the uprising.

The party was founded in 1905 as a monarchist home rule faction not as a separatist republican organization and by 1916, little had changed. Their leader, Arthur Griffith, supported the uprising, but neither he nor many party members participated. Over the succeeding years the party was taken over by extremist republican figures as a result of a repressive government response and increased radicalization. By 1919 it was the primary mover behind a separatist Irish parliament and the creation of the Irish Republican Army.

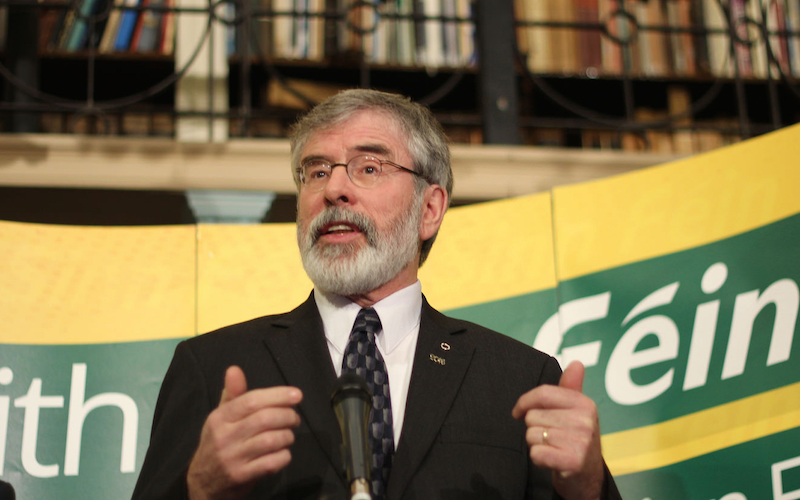

In 1921 Sinn Féin’s split resulted in the Irish Civil War which was won by the moderate faction (who became Fine Gael). The extremists then largely withdrew from politics in the south of Ireland and became synonymous with the troubles in Northern Ireland. While still a registered party in the Republic of Ireland, they continued to abstain from taking any seats won in any parliament or council, whether in the Republic, Northern Ireland, or Great Britain. This situation changed in the 1970s and 1980s when they split over abstention. Sinn Féin, led by Gerry Adams, finally took seats in the Dáil. The next decades saw the party continuously grow in the Republic to the point that it is now the fourth largest party.

It appears that Sinn Féin has done well, but does not have the numbers to lead the formation of their own government. The problem for Gerry Adams is that no others runners seem willing to form a government with them. Their relationship with Fine Gael and Fianna Fail; both of whom were once allies with Sinn Féin in the early 20th century, is still poisonous, rooted in historical animosity. Other leftist parties such as the Social Democrats, Labour, and the Anti-Austerity Alliance won’t work with them either.

This reluctance is not necessarily ideological nor political but rather more personal. Many of the other leftist parties and even the liberal wings of Fianna Fail have policies that are not dissimilar from Sinn Féin’s manifesto. Sinn Féin’s problem is its history, legacy, and its leader. Recent party leaders’ debates have demonstrated that the party’s links to militant republicanism, murder, and the Provisional Irish Republican Army remain a stumbling block. Gerry Adams has been consistently hammered by his adversaries for past events such as the murder by the IRA of Irish police officers, the Northern Bank robbery, and a litany of IRA crimes against humanity that took place under his watch in Northern Ireland.

The real problem for Sinn Féin may be Adams himself. As much as he refutes claims of past membership in the IRA, most people in the Republic don’t believe him. There is also a belief that he knows much more about a spate of murders and disappearances many of which have recently been unearthed (literally). The feeling is that if Sinn Féin is serious about moving into the future and finding coalition partners, Adams’ position as party leader will seriously have to be considered.

Until this happens, the party can only wish for permanent opposition in the Dáil. How long moderate members and back benchers in their ranks will be satisfied by this limitation remains to be seen. In all likelihood a Fine Gael and Labour coalition will return as a minority government.

Amazingly, this may involve a coalition with Fianna Fail. Irish politics have been dominated for 80 years by Fine Gael and Fianna Fail to the point where it seemed that a two-party system was in place. The fact that these two traditional main parties and rivals are willing to work together while spurning Sinn Féin demonstrates the degree to which Adams and his cohorts are seen to be tainted by blood and history.

The challenge for Sinn Féin is how they react after the final votes have been counted. Unable to lead a government alone, at least not for another generation, they badly need friends to have any hope of governing. Gerry Adams will have dreamed all his life of being center stage when the 1916 celebrations take place. But, like Sinn Fein in 1916, Sinn Fein in 2016 may have no part to play.