The Evolution of Displacement: A Jew in Iraqi Kurdistan

I can’t help but be moved by the mountains that greet me from the window of my motel. It’s late June and I had just made the trip from Erbil, the capital of Iraqi Kurdistan, to Dohuk, a northern city, 30 miles from the border with Turkey and Syria. I wonder how much history these mountains have witnessed: from the ancient fall of Assyria, to Saddam Hussein’s modern reign of terror, and now the savagery of ISIS. I have come here on a pilgrimage of sorts—I am heading to the purported tomb of the Jewish prophet Nahum, housed in a synagogue that lies on the outskirts of the village Alqosh.

Ensconced in the Bahidrya Mountains, the village has been inhabited for more than 25 centuries, and is home to the oldest Christian communities in Iraq and the Middle East—Chaldeans and Assyrians. The village’s inhabitants, known as Alqoshnayes, which translates to “those of the God of Righteousness,” still speak Aramaic. Jews were brought to Assyria beginning in the 8th and 9th century BCE, following the Assyrian monarch Sargon II’s conquest of the northern kingdom of Israel. Iraqi Jews continued to make pilgrimages to this site until 1950, when following the creation of the State of Israel, the majority of Iraq’s 130,000 Jews immigrated to the Jewish state.

To the Jews, the land between the Jordan River and the Mediterranean Sea is holiest; yet due to repeated exiles at the hands of conquering empires, Jews became known as “a people without a land.” Jews adjusted to this reality in these very hills—‘beyond the river’ or ever ha nahar, the biblical Hebrew term that denotes the region along the Euphrates, modern-day Iraq.

After being expelled from Jerusalem, following the fall of the second temple in 70 AD, Babylon would become the spiritual, religious, and cultural epicenter of Judaism for more than a thousand years to come. Despite the perennial longing for Jerusalem, Jewish life flourished here.

Babylonian academics outshone their Galilean counterparts, evident in the emphasis placed on the Babylonian Talmudic texts.

It is here that the Jewish Oral Law, torah she ba’al peh, passed down throughout generations—the laws were not merely codified, but the inhabitants of these cities were entrenched in lively and contentious debate. Conversations from 450 CE that we are still engaging in today originate from these cities– Pumbdedita (current day Fallujah), Sura, Nehardea—they housed the great Yeshivas that gave rise to the Bablyonian Talmud.

“Nahum,” in Hebrew, means comfort, and while reading his prophesy during my ride to the village, I searched for consolation in his words. For my own sanity, for the belief that one-day the Iraqi people will find comfort themselves. Nevertheless, my optimism is tested in this place. When you’re able to put face to face with the ugliest manifestations of what humanity is capable of; how life is cheap. It has now become impossible to find an Iraqi family that hasn’t been affected by the violence. The international media barely reports on the continued loss of Iraqi life; attacks which are weekly occurrences, and have been for the past 10 years.

“Spilled blood and superstition are the basis of the world,” posits the esteemed Iraqi writer, Hasin Blassim. Maybe he is right. It is what drew me here originally, to gain a firsthand insight into the suffering, and resilience of these people who have borne the brunt of decades of war. When you encounter it face-to-face—the depravity, and cruel and inhuman ignominy—it is easy to be repulsed. My gut reaction is one of caution: I am exposed to a place, a world, that on so many levels I was not meant to see—as an Israeli, a Jew, an American. But, unexpectedly, without realizing, the fear and doubt dissipate. The selfless generosity and hospitality I have encountered throughout my visit reminds me that all just wants to have their voices heard—to share their story. That I can do. I can listen.

Israeli historian Irad Malkin theorizes that history is the consciousness of the constantly evolving relationship between continuity and change. Jews insist on forging a connection to our past in biblical Israel, through the dynasties of Judea and Samaria, and cultivating the land of Israel. What can be made of the Jewish history of Iraq, and the other Arab lands from which Jews were exiled? Who is entrusted to enshrine this history? Does this same revival not apply to Iraq—or does the current narrative negate our ability to forge a connection to our ancient past?

Jews hold a legacy of two thousand years of persecution, which engenders a sentiment that eloping on an emotional journey to the past is an exercise in futility. ‘We were kicked out, persecuted, shamed’– the common refrain holds that we don’t belong here. I am not denying the obvious enmity that exists between Arabs and Jews, but neither am I constrained by it. More pertinent however, it would seem as if the fate of my Assyrian hosts is linked to that of the Jews. From the peak of the mountains in Alqosh, that overlooks the northwestern plain of Nineveh, you can spot Mosul, and the frontlines between the Kurdish Peshmerga and ISIS.

My guide, an Assyrian human rights activist, a native Alqoshayen, now lives in a similarly dry and desolate landscape, albeit one inhabited by casinos and capitalism— in Las Vegas, Nevada. Figures hold that a third of Iraq’s 1.5 million Christian Assyrian population has left Iraq, with less than 500,000 remaining, as the result of years of persecution at the hands of Al Qaeda, and ISIS. Since Mosul’s fall last August, the topic has garnered unprecedented attention. Does the future of Christians in the Middle East mirror that of the Jews? This is not merely an ideological battle of Christianity versus Islam: the cultural legacy and future existence of a thousand years old religion in the cradle of civilization is at stake.

The lives of Iraq’s Christian minority were fraught long before ISIS entered the scene. Nestled between Iraqi and Kurdish claims, they were persecuted under Saddam’s Arabization policy. And since the recent de-facto disintegration of Iraq, Kurdish Peshmerga have laid claims to many of these villages, as part of the larger disputed territories question.

As we sat in his cousin’s living room, under flashing red and white orbs outlining a poster of Jesus, my host relayed his true fears. What will the future of Iraq look like? By erasing the historical references, ISIS is attempting to re-write history. Jews and Christians had been settled in these lands for centuries before Islam, and yet the past 50 years have seen their numbers more than halved. Without this past, how will Iraq be defined?

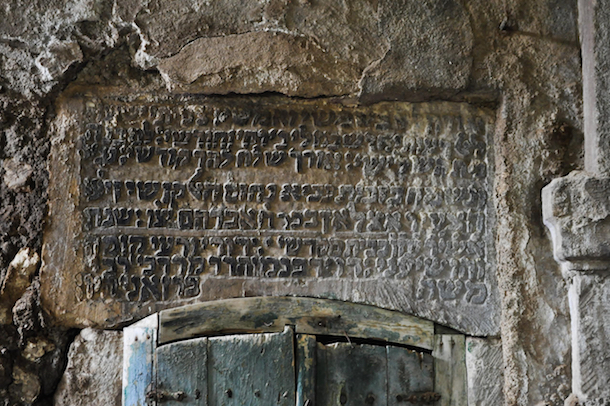

Our host took us to meet the village Priest, Father Aram, a man in his thirties, who gives us a tour of two monasteries, one dating back to the 5th century. He seems to have understood that we didn’t journey to this remote village to visit the monasteries. Leading us down a narrow alleyway, we come to a large cement door, protected with a padlock and chain. The keys to the synagogue were entrusted to his family for over half a century, since the last Jews of the village fled. Entering through the gateway, into what used to be the synagogues courtyard, a half crumbling stone structure takes form in front of me. On top lies a red metal awning recently built to protect visitors on the inside. It’s aesthetically underwhelming, until I realize that this is the last standing relic of Kurdistan’s 3,000 Jewish history.

I descend a staircase that leads us into the Synagogues main chamber—in front of me lies an altar, covered in a green tarp. I open my pocketsize book of Psalms to a random page:

“My enemies shout at me,

making loud and wicked threats.

They bring trouble on me

and angrily hunt me down.

My heart pounds in my chest.

The terror of death assaults me.”

I imagined how this refrain echoes the feelings of those currently suffering at the hands of ISIS. From Iraq, to Syria, to Yemen—it is easy to feel as if war runs in their blood—yet all Abrahamic religions carry a legacy of conflict. It is our job now to focus on the precepts that unite us: the sanctity of life, the ability to ask and grant forgiveness, the dignity of the individual, and resolve for nonviolent methods of conflict resolution. As inspiration I return to a quote of Albert Camus, one of the 21st centuries most revered humanists: “I have always thought that the maximum danger implied the maximum hope.” We stifle and yet survive, we think we are dying of grief, and yet life wins out.

Despite the fact that Jews no longer inhabit these lands—Nahum’s prophecy provides consolation. Apart from the cruelty the Jews suffered at the hands of the Assyrians, God provides a refuge in times of trouble.

For many Iraqi’s, that refuge has been Kurdistan. Out of Iraq’s three million displaced people, one million have taken up residence in Kurdistan, either in internally displaced peoples (IDP) camps, or housed and welcomed by the urban populations. For all its brutality, ISIS has also granted the Kurds legitimacy, as they are one of the few groups who been able to effectively fight the group.

The spotlight however will soon turn to how they treat their own minorities, and the displaced peoples under their control. After discussing the future with IDP’s I met while volunteering in these camps—whether Christians, Yazidi, Sunnia or Shia—they voiced a shared sentiment. That good will prevail, redemption will come, and their children will live to see peace.

Faced with such triumph of spirit, I ask myself what right do I have to be disconsolate about the situation here? Those for whom this is day-to-day reality don’t have the time or space to indulge in despondency—they have to carry on living, to take care of the their children.

Our job is not to give into such despair—but rather to help man fight against what is oppressing him with compassion and faith. This is a reality the Jewish people have known throughout time: families torn apart by war, persecuted on the basis of faith, struggling to maintain dignity in the face of impossible conditions, and the eventual resignation to rebuilding your life somewhere new.